The Great Detective: The Amazing Rise and Immortal Life of Sherlock Holmes is a sprightly, riveting exploration of Sherlock Holmes—and the character’s thriving, eccentric subculture. Zach Dundas, the book’s author, reveals that the frenzy surrounding Sherlock isn’t strictly a Benedict Cumberbatch-related phenomenon. The master of Baker Street, who was born on January 6, 1854, has always inspired fanatical devotion and feverish anticipation. Here are 15 details about literature’s greatest detective, as revealed in The Great Detective.

1. There is a Sherlock Holmes equivalent of Trekkies.

The Print Collector/Getty Images

There are as many as 300 societies dedicated to Sherlock Holmes. Devotees of the detective call themselves Sherlockians or Holmesians. There is some division in their ranks as to how the terms should be applied, though generally speaking, American fans are Sherlockians and British fans are Holmesians.

2. Sherlock Holmes societies are a kind of literary United Nations.

Perhaps the most prestigious Sherlock Holmes society is the Baker Street Irregulars, an invitation-only organization that was originally named for Holmes’s intelligence network of homeless children. Other clubs include the Sherlock Holmes Society of London, the Bootmakers of Toronto, the Great Herd Bisons of the Fertile Plains, and the Seventeen Steppes of Kyrgyzstan. There are also trade-specific Sherlock societies for such groups as poets, psychologists, and mathematicians (“the last named for Moriarty, of course,” Zach Dundas writes).

3. Sherlock Holmes’s influence was vast among elite writers.

T.S. Eliot said, “Every writer owes something to Holmes.” John Le Carre described the short stories as “a kind of narrative perfection.” Dorothy Sayers even wrote a treatise on Watson’s name, attempting to work out how it changed from John H. Watson to James in a later story. She eventually speculated that the middle initial H is short for Hamish, the Scottish form of James. (This is the convention used in the television series Sherlock.)

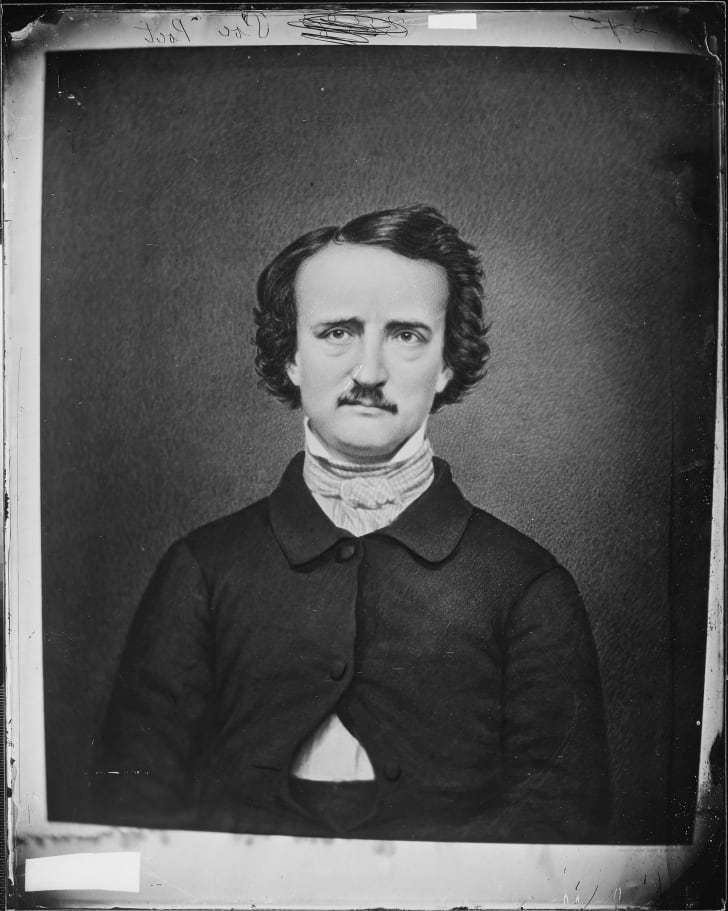

4. It all started with Edgar Allan Poe.

Detective fiction was still in its infancy when Arthur Conan Doyle wrote his stories. Edgar Allan Poe introduced to the genre the concept of a single detective whose cases span several stories. Later, Wilkie Collins elevated the genre with his serials. Conan Doyle brought together the forms of the genre, elevated it with his prose and pacing, and modernized it by having his protagonist use science as part of his investigation. The first character in fiction to use a magnifying glass to help solve a case? You guessed it.

5. The proto-Sherlock Holmes was a doctor …

When Conan Doyle began sketching out the character, he thought back to his medical school days and recalled a professor with an astonishing eye for detail. Dr. Joseph Bell was known to make accurate diagnoses of his patients from such details as patterns of wear on trousers, bearing, and general disposition. “All careful teachers have first to show the student how to recognize accurately the case,” Bell explained. How stunning was the Bell-Holmes resemblance? Upon reading a Sherlock Holmes story, Robert Louis Stevenson, a fellow student of University of Edinburgh, wrote Conan Doyle a letter complimenting the character and his adventures, and asking in closing, “Can this be my old friend Joe Bell?”

6. … Or maybe Sherlock Holmes wasn’t a doctor.

The “St. Luke Mystery,” a sensational, real-life case in 1881 in which a London baker disappeared, might have in some way inspired Conan Doyle. A German named Walter Scherer was brought on to help investigate the incident. He described himself as a professional “consulting detective”—hardly a commonplace professional description, and the same one that would eventually describe the man working from 221B Baker Street. Some, most notably author Michael Harrison, argue that Scherer, not Bell, was the model for Sherlock Holmes.

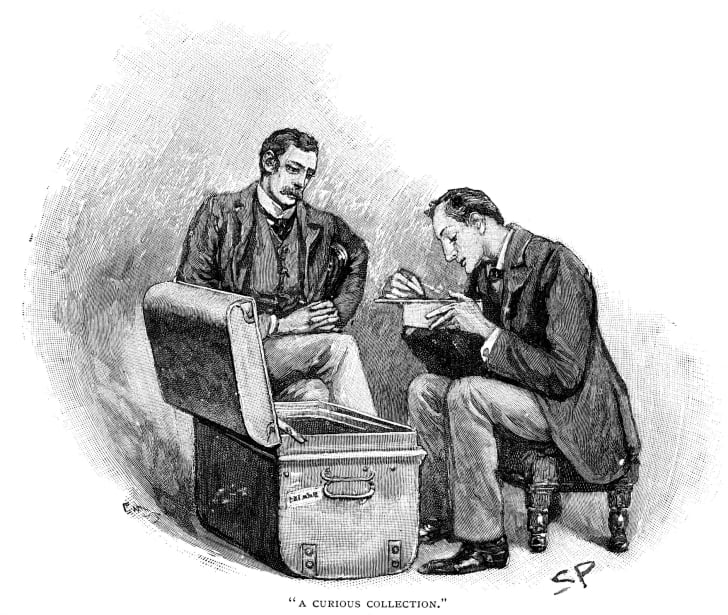

7. Arthur Conan Doyle popularized a new storytelling format.

Photos.com/iStock via Getty Images

When Conan Doyle wrote his short stories, he recognized that serial narratives were falling out of favor with readers—it was too easy to miss one issue and thus lose one’s place in a continuing story. For his Sherlock Holmes stories, he developed a format in which the characters and general circumstances would remain the same, but each story would be standalone and able to be read in any order.

8. Sherlock Holmes was the original success kid.

Long before we took to Twitter to write, “I believe in Sherlock Holmes,” the detective was a viral sensation. One year after publication of “A Scandal in Bohemia,” the first Holmes short story, some magazines were already parodying the character, some were publishing thinly-disguised rip-offs, and theatrical companies were performing the character in unauthorized stage productions.

9. The hunt for 221B Baker Street is ongoing.

Part of the allure and longevity of the Sherlock Holmes short stories are their settings. Holmes’s London is real and thriving, and the places in which he has his adventures are real places. His apartment, 221B Baker Street, however, is fogged in mystery. When the stories were written, Baker Street addresses did not go as high as 221, and Conan Doyle refused to divulge the building’s inspiration. For nearly a century, scholars have worked hard to uncover it, going so far as to subject the numbers mentioned in the Holmes texts to Voynich-Manuscript-level scrutiny, and even mapping the backyards of Baker Street, comparing them to details mentioned in the text.

10. Sherlock Holmes’s cases are not true crime stories.

Conan Doyle’s historical novels were meticulously researched. As The Great Detective notes, to get the details correct, the author might read “hundreds of volumes on, say, English archery, or Napoleon.” The Sherlock Holmes stories, however, were dashed out as quickly as four in two weeks. In “Adventure of the Speckled Band,” for example, Holmes determines that the murderer controls a snake with a whistle and a bowl of milk. As Zach Dundas writes, “snakes can’t hear and don’t drink milk. Does anyone care?”

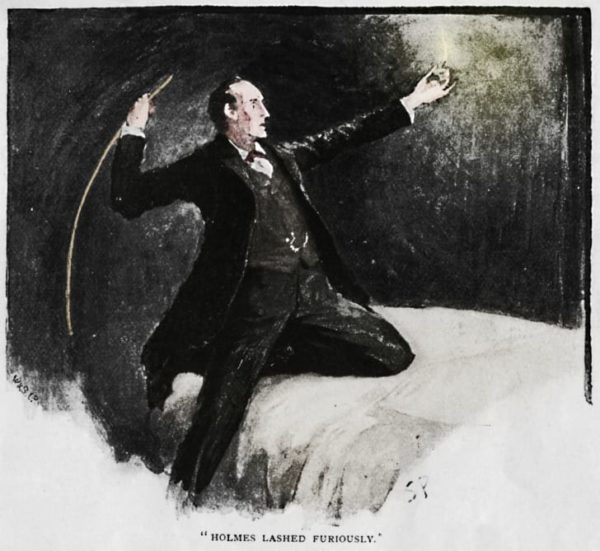

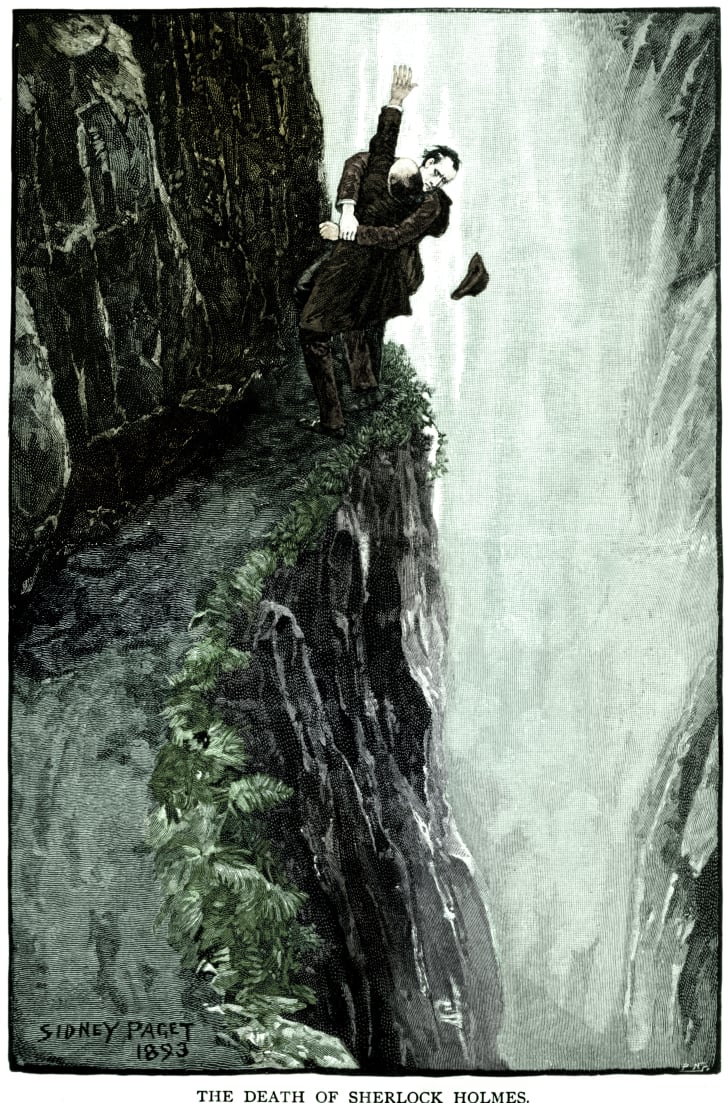

11. Arthur Conan Doyle was on a nature hike when he decided how Sherlock Holmes would die.

The Print Collector/Getty Images

The fabulous success of Sherlock Holmes might eventually have become a bit too much for Conan Doyle, and to get on with his life he eventually resolved to kill off the detective. Just about everyone begged him not to, from his mother to his publisher, but his mind was set on it. He only needed a death suitable for his icon. While vacationing in Switzerland, he and a group of friends went hiking. When they came upon Reichenbach Falls, Conan Doyle decided that it was a fitting grave for Sherlock Holmes.

12. But the great detective wasn’t done yet.

At the time of Holmes’s untimely death, Conan Doyle was a wealthy man and a fixture of society. Years later, his spending began outpacing the growth of his income, and returning to Sherlock Holmes became an appealing option. Rather than raise the detective from the dead, he authorized a stage production based on Holmes. In 1901, Strand magazine began serializing The Hound of the Baskervilles, a new Holmes novel written by Conan Doyle. (To get around the thorny problem of Holmes having plummeted down Reichenbach Falls, the novel was set in a time previous to that story.) In 1903, Collier’s Weekly made Conan Doyle an offer: $1.3 million (in 2015 money) for a new series of Sherlock Holmes stories. Conan Doyle’s response, by postcard: “Very well.”

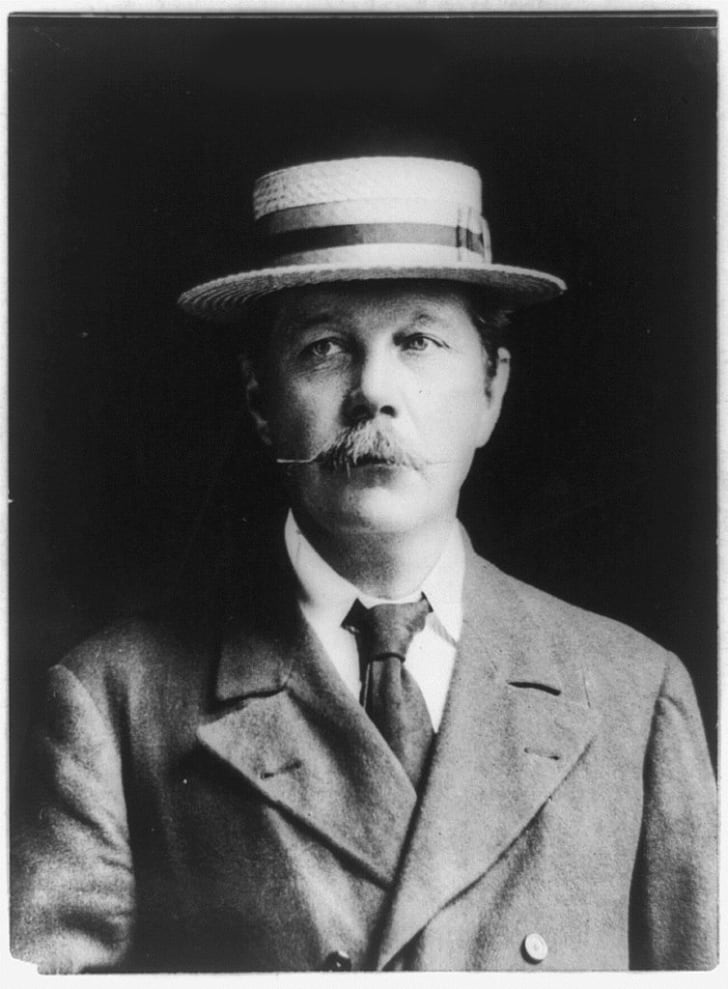

13. Arthur Conan Doyle: father to Sherlock Holmes—and peer?

During his lifetime, Arthur Conan Doyle did a little bit of everything, from transforming literature to running for Parliament to playing competitive sports. But Conan Doyle has had a post-death nearly as active as his life. Sherlock Holmes lives on, of course, but Conan Doyle has also become a compelling character in fiction. On the page, stage, and screen, the author can be found solving crimes that no one else can.

14. Arthur Conan Doyle’s sanity was questioned.

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Toward the end of his life, Conan Doyle embraced spiritualism and invested considerable capital, both personal and financial, in spreading the message. He frequented psychics and mediums, held séances, and argued the existence of fairies, defending even the worst photographic forgeries of the winged sprites. One headline at the time summed up the situation, asking if the author was “hopelessly crazy.”

15. Sherlock Holmes was first in peace, first in war, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.

Though Conan Doyle couldn’t conceive of Sherlock Holmes in a world post-World-War-I, the great detective saw quite a bit of action during World War II. As noted in The Great Detective, Holmes appeared in British propaganda videos; one of his stories was required reading for soldiers in the Soviet army; Britain’s wartime spy agency set up shop on Baker Street and called themselves the “Baker Street Irregulars”; and one of the two films found in Hitler’s bunker was The Hound of the Baskervilles.