The scene that greeted Patrick Santos’ father was something no parent should ever have to see.

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

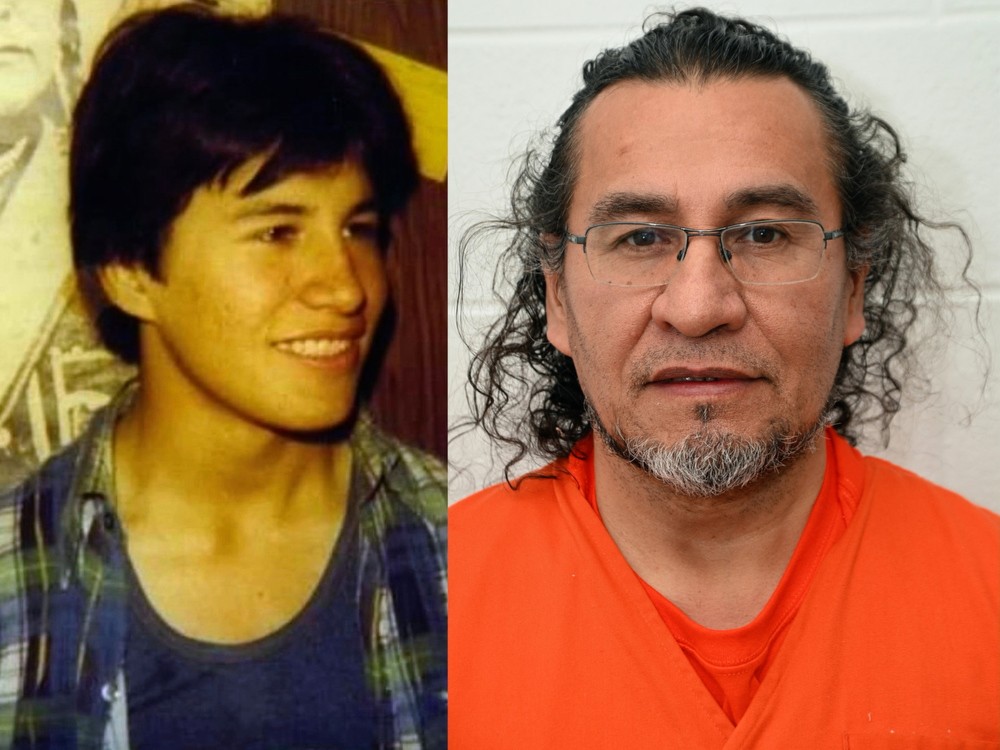

On Sept. 17, 2006, Santos’ dad opened the back door of his Scarborough home to let the family dog out and discovered his son’s lifeless body on the ground.

Duct tape covered Patrick’s face and his hands and feet were bound. He was only 21 at the time of the murder.

The cause of his death was determined to be suffocation.

For almost 17, the Santos murder has remained a mystery.

Cops are certain there are “many” who know why the kind young man was murdered. They’re just not talking.

As Nick the bartender said in It’s a Wonderful Life, all they need is a “convincer.” That convincer is DNA and genetic genealogy.

“We know we can solve this, it’s one that really bothers me,” Toronto Police Det.-Sgt. Steve Smith recently told The Toronto Sun, “then again, they all do.”

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Smith has been head of the Homicide Unit’s cold case squad for the past five years. During that time, three of the city’s highest-profile unresolved homicides have been cleared.

In 2020, cops cleared the shocking 1984 sex slaying of 9-year-old Christina Jessop. It was the little girl’s neighbour, a guy named Calvin Hoover. Unfortunately, he topped himself in 2015 and will never face justice on this earthly plain.

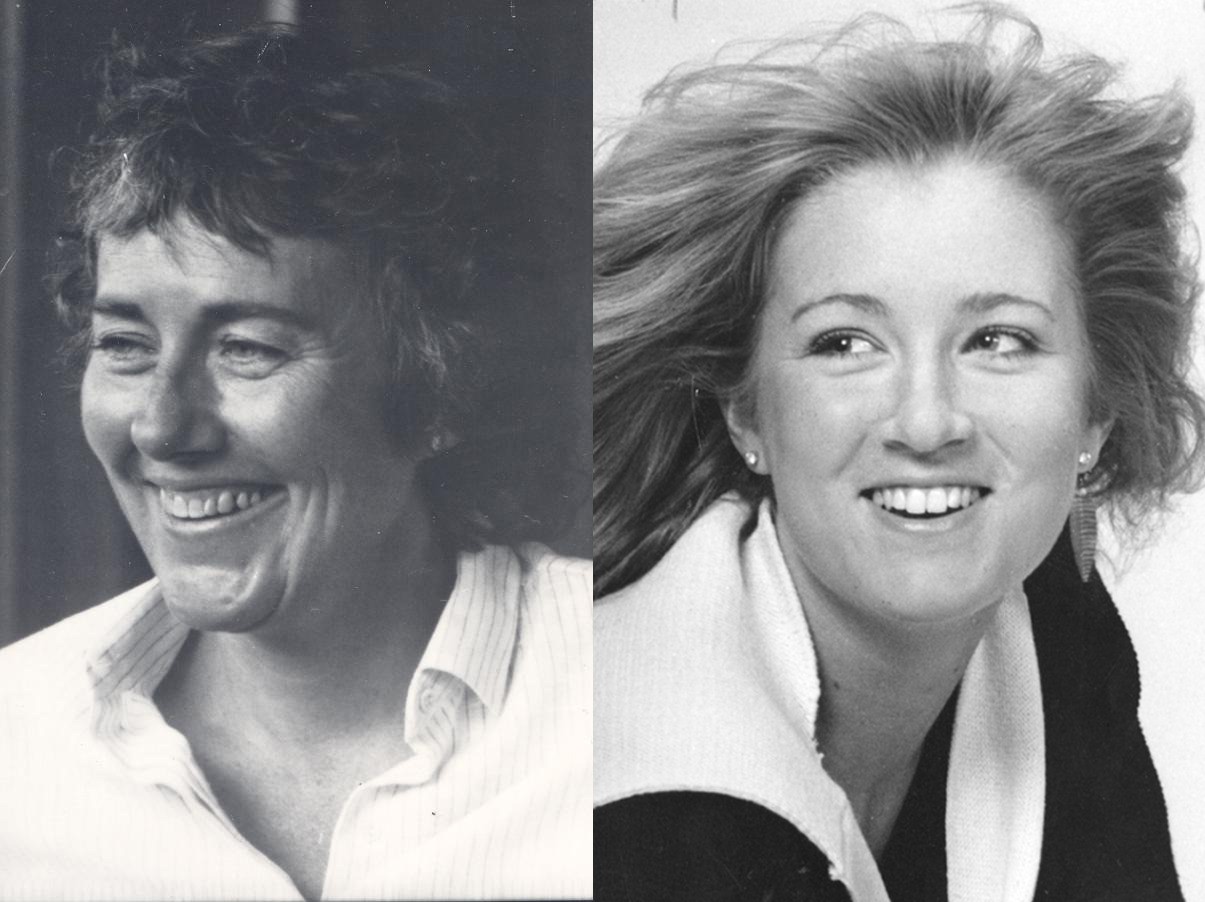

And in December, police announced an arrest in the 1983 murders of single mom Susan Tice and socialite Erin Gilmour. The suspect — Joseph George Sutherland, 61, of Moosonee — was never on cops’ radar.

Smith noted that finding him “would have been like looking for a needle in a haystack” if not for one thing: Genetic genealogy.

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Any crime scene where DNA has been left behind now has the potential to be solved with this “game changer.”

“The Solicitor General’s office has given a grant for us to submit 30 sets of DNA for genetic genealogy testing in 2022 and another 30 in 2023 . That includes unsolved murders, sex assaults and unidentified human remains,” Smith said.

Fifteen of the sets will be from Toronto cops, the other 15 from police services around the province.

What the genealogical tests do is narrow the suspect tree by tens of millions using websites like Ancestry.com and 23andme. The tests narrow the DNA to a family group. After that, it’s old-fashioned shoe leather.

“We have DNA from families back to the 1970s and ’80s,” Smith said, adding that previously if a suspect’s DNA was not in the system, then detectives were left empty-handed.

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Missing persons and unidentified human remains would be almost impossible to solve using the old methods. In addition, Smith said cops are working on a national clearinghouse for the missing.

“This is significant because it finally puts together missing persons cases from across Canada and it’s becoming very organized,” the veteran detective said.

Santos is among the cases cops have submitted for testing, along with DNA from a number of the notorious unsolved sex worker murders from the 1980s and 1990s. Also on the list is little Rosedale Jane Doe whose lifeless body was discovered in a dumpster in the posh neighbourhood last spring.

There are 64 other sets of unidentified remains in Toronto stretching back decades.

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

In addition, cold case cops are constantly resubmitting DNA for testing because of the rapid advances in the field. An example of this was Philadelphia’s 1957 Boy in the Box murder.

Investigators had been stymied by the tragic case for decades. Even with the arrival of DNA as a crimefighting tool, it wasn’t enough. Until it was and the four-year-old victim was identified as Joseph Augustus Zarelli.

“There are so many different applications for this,” Smith said. “There are only so many things that DNA will actually tell you. Once you’ve developed a pool of persons of interest the rest is up to investigators.”

He added: “Then, you have to follow the evidence and put your theories into action.”

Part of the emerging piece will be the nascent Missing Persons Unit, which “morphed from a compliance unit to a proactive investigations unit.”

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Smith noted that there are several hundred long-term missing persons cases, the oldest being the mysterious 1919 disappearance of theatre impresario Ambrose Small.

“It a lot harder to go missing now, to just disappear,” the detective said. “With all the cameras and digital tracking.”

Referring to the notorious Bruce McArthur serial killer case that featured an overwhelming missing persons component, Smith said there are more checks and balances in disappearances now. He added that those new legislative checks and balances were already coming into play at the height of the McArthur probe.

“With these new tools and old-fashioned detective work, we’re hoping to give the devastated families of the murdered and missing an element of closure,” Smith said. “And those answers are going to come sooner rather than later.”