On Oct. 24, 1987, bird hunters found human remains in a remote wooded area of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Classified as a homicide, the cause and manner of death is undetermined.

And 36 years later, the victim, “Luce County John Doe,” remains unidentified.

Michigan State Police in alliance with the DNA Doe Project (DDP) continue seeking answers, but they need help from the community.

“We have a saying that you can’t solve your homicide without first knowing who your victim is,” said Hanna Friedlander, a human remains analyst who works in the Intelligence Operations Division of Michigan State Police.

Meet John Doe

“The Luce County Doe was found in Newberry, Michigan, right in McMillan Township in a wooded area,” Friedlander said.

Friedlander cannot comment on the details of the homicide. But she said the remains were mostly skeletal, dressed in military-style clothing. The victim wore a camouflage jacket, pants, green camouflage t-shirt, green belt, green wool socks and black combat-style boots.

“The clothing is military-style clothing, (but) it doesn’t mean that it’s from the military. Most likely we are looking at someone who is out hunting or in the woods doing some sort of survival skill lesson for themselves. It’s really hard to say,” Friedlander said.

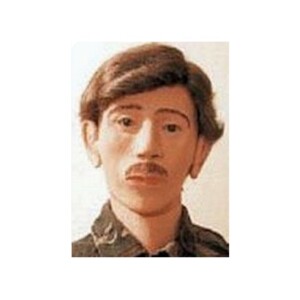

John Doe was a Caucasian male, 20-35 years old. He was about 5’8” tall with short, reddish-brown or auburn hair. The deceased had an injury that required a metal rod to mend a broken leg years before his death.

The man died four months to two years before being found.

Identifying John Doe

Friedlander’s job as a forensic anthropologist is to search, locate and recover unidentified remains, including victims of homicide, suicide or accidental deaths.

“I help identify them through the collection of biometric data such as fingerprints, dental and medical records or using DNA such as forensic genetic or investigative genetic genealogy to help make sure we have a complete profile of the individual,” Friedlander said.

After collecting the sample, DDP analyzes it.

DDP, a volunteer-run, nonprofit organization, identifies and returns John and Jane Does to their families. One recent success story was that of Dorothy Lynn Thyg Ricker, who washed up on a Lake Michigan beach near Manistee in 1997.

Gwen Knapp served as the DDP team leader on the Dorothy Lynn Thyng Ricker case.

“The genealogy process of identifying Dorothy was relatively quick,” Knapp said. “The team was able to narrow in on a family of interest within a day thanks to having solid family matches in GEDMatch.”

Genetic genealogy service GEDmatch accepts data from all direct-to-consumer DNA testing companies, though it is unaffiliated with any of them. Users compare their DNA results to people who have tested with other companies.

For unidentified remains, the GEDmatch program uploads their DNA profiles. Then begins the process of building their family trees and triangulating DNA segments to find the ancestry couple.

Luce County John Doe is missing familial matches in the GEDMatch system, however.

The community can help

“These cold cases can be particularly difficult because a lot of the immediate family that know these individuals are either deceased themselves or have given up hope. With the development of new technologies, getting older generations to upload DNA to those databases such as GEDMatch becomes more challenging,” Friedlander said.

Knapp explained that having the public upload their at-home testing material could be the breakthrough they are waiting for in many Jane and John Doe cases.

“We need people to take their Ancestry test or their 23andme test and upload it GEDMatch so we have better matches,” Knapp said.

“It’s important for individuals that are considering doing genealogy on themselves to figure out who their distant relatives are, to be mindful and open to sharing their DNA with law enforcement on companies such as GEDMatch because it helps us pinpoint who these unidentified persons are and return them to their families,” Friedlander said.

“I look it as you are helping give someone back their missing loved one, and that’s probably one of the greatest gifts you can give that family, closure, and knowing where their missing loved one has gone off to all these years,” she added.

Nationally, DDP has solved nearly 100 missing person cases. Currently the Michigan State Police have 330 open unidentified cases.