Alice Collins Plebuch, or Grandma Nerd, as her grandkids call her, is good at solving puzzles. She was among the first wave of computer programmers—when that term meant punching information on cards to be fed into mainframes. She has an analytical mind and is at ease with technology. Years ago, she began digging into her father’s history, hoping to find more about the man who’d grown up in an Irish-Catholic orphanage in New York. So once the paper trail hit a dead end, she turned to an at-home DNA test.

It was 2012, and Ancestry had just released a beta version of its first spit kit. Back then, the results just gave users rough estimates about their ethnicity. And when Collins Plebuch’s results came back in the mail, at first she didn’t believe them. Instead of the 100 percent British Isles heritage she expected—Irish on her father’s side; Irish, English, and Scottish on her mother’s—that turned out to be only 48 percent of her genetic makeup. The rest was a mix of what the company called “European Jewish,” “Persian/Turkish/Caucasus,” “Eastern European,” and “other.”

Over the next few years, those results would lead Collins Plebuch to disinter a long-buried family mystery: the real reason why her father didn’t look like the rest of his family, and why Collins Plebuch didn’t look like the kids in the Irish Catholic families she grew up with. The discovery led her to more relatives and yet more spit kits. Her search to understand where her father really came from would extend across years and continents. Ultimately, this great adventure would lead to surprises both happy and sad, and forever redefine her notion of family.

In 2017, journalist Libby Copeland wrote about Collins Plebuch in a feature for The Washington Post. Overnight, emails began to flood Copeland’s inbox, hundreds of them, from people who wanted to tell her about how DNA testing had affected their own lives in profound ways. She received letters from adoptees who’d gone searching for their biological families, and from sperm donors who hadn’t—but who got found anyway. Some people discovered they’d been conceived through rape or incest. Others had gone looking for their family history but had only turned up more questions.

That’s when she started to wonder if maybe the rise of databases connecting millions of people through their shared DNA was bigger than the story of one family. Maybe, she realized, America was in the midst of a vast social experiment that nobody knew they had signed up for.

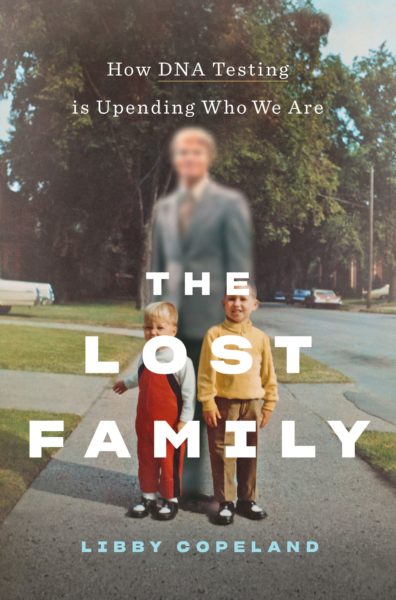

It is into this world of “seekers,” spit kits, and retooled family trees that Copeland plunges in her new book, The Lost Family, which publishes today. Copeland takes readers inside America’s first DNA testing lab dedicated to genealogy, to Salt Lake City’s Family History Library—the largest genealogical research facility in the world—and into the living rooms of dozens of people whose lives have been turned upside down due to the results of a recreational DNA test. It is at once a hard look at the forces behind a historical mass reckoning that is happening all across America, and an intimate portrait of the people living it.

Copeland sat for an interview about how the simple spit kit has sent the past irrevocably careening into the present. It’s been condensed and edited here for clarity.

WIRED: First of all, this book was such a treat to read! Alice Collins Plebuch’s dogged pursuit of her family mystery has so many unexpected twists. But her search also personifies this much broader phenomenon brought on by DNA testing. In the book you describe it as a sort of forced reconciliation with the past. Can you explain what you mean by that?