9

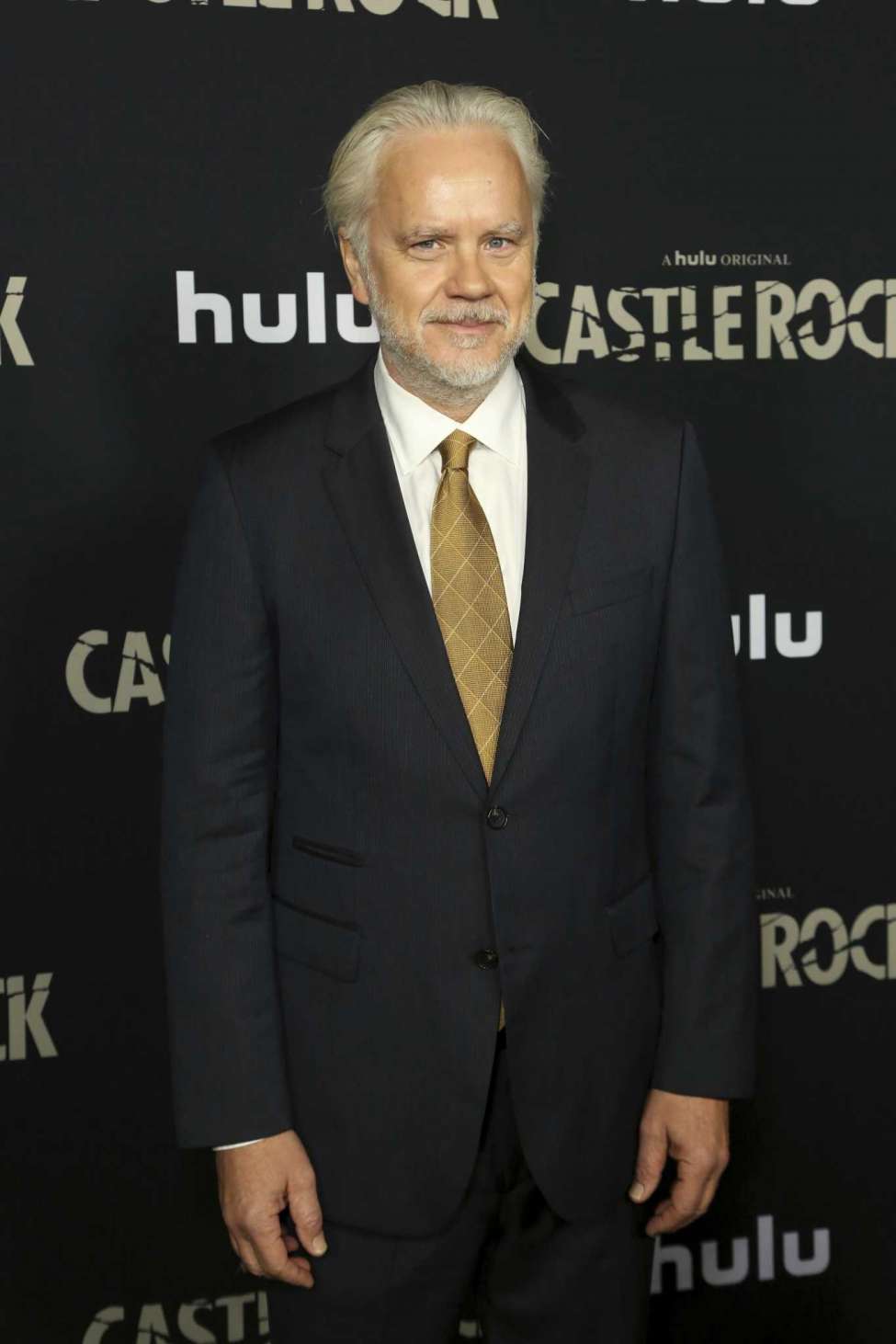

Twelve actors telling 12 stories in 12 languages: “The New Colossus” has a lot to say about America, the immigrant experience and the ties that bind in a time of discord. So does its co-writer and director, Tim Robbins.

“Everything’s so divided. We’re trying to tell stories that remind us that everyone has a shared humanity,” says Robbins, who’s traveling with the Actors’ Gang theatrical troupe — which he helped found — on a short tour that includes two shows at Proctors.

At each stop, a map of the world sits in the lobby, filled with magnetic pins showing audience members’ countries of origin. And at each stop, Robbins walks out at play’s end to spark conversation with the crowd.

Who’s descended from indigenous peoples? A few hands go up. Which nations? Cherokee. Navaho. Is anyone here descended from people brought against their will? African-Americans raise their hands.

Any refugees? Immigrants? Hands go up. Any sons and daughters of refugees and immigrants? More hands go up. Grandsons and granddaughters? More still. Eventually, he says, “The entire audience has put up their hands. That’s our shared experience in this country.”

Robbins is on the phone from his home in Los Angeles, where he just got back from a frustrating trip to the DMV. “Oh, my God, it didn’t work out that well for me.” See, he’d just bought a Volvo, and it was a lemon, but he couldn’t get a refund without a title, and motor vehicles told him he had a lien on the car, which was ridiculous because he paid cash for it, and … so on.

“This is why I have a sense of humor at this stuff,” he says, sounding resigned. “I used to get angry at this sort of thing.”

The Tim Robbins on the phone is pretty much the Tim Robbins you’d expect: Funny, political, loquacious. The actor known for iconic roles from “Bull Durham” to “The Shawshank Redemption” — and lately seen in “Dark Waters” — talks, and he talks, and he talks, expounding on the play, its themes and humanity itself over an hourplus interview that was only meant to last 30 minutes. Short answers morph into long ones, filled with reflection on immigration and the American character.

Co-written with the Actors’ Gang, the play bears witness to the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” immortalized in bronze at the Statue of Liberty. Emma Lazarus’ hopeful sonnet shares more than just a title with the production, which aims to honor the immigrant spirit in the midst of divisive political rhetoric. “That’s something we should celebrate. That’s the heroes’ journey, and that’s what unites us with the people at the border to the south. … They’re trying to provide a better future for their kids, and what are we doing? We’re demonizing them.”

None of that is anything new, he says: Not so long ago, Irish and Italians felt the brunt of it. “I’m sorry that people fall for that. It’s tragic. But one of the reasons that I wanted to do this piece was to remind people that we have a lot more in common than we have differences.”

The idea for it sprang, several years back, from an Actors’ Gang production of Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” The cast included actors who spoke English as a second language and wrestled with the ornate Elizabethan phrasings. “I wanted to find a piece that I could do with these great actors that wasn’t as reliant on the English language. … so I started asking them to tell stories in their native tongue.” Then he asked them to write tales based on the lives of their forebears — “to tell the story of their ancestor’s journey from oppression to freedom.”

In the play that resulted, actors inhabit their own parents, grandparents, ancestors — strivers and survivors from Iran after the 1979 Revolution, from Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union, from Vietnam after the fall of Saigon. In one story, a black woman flees the KKK during Reconstruction; in another, a Jewish woman flees the Nazis just before World War II.

What underpins their stories, he says: “Strength.” That’s the short answer. The long answer: “First of all, just to say ‘no’ in their home country. ‘No, I will not tolerate religious oppression. No, I will not tolerate oppression. No, I will not tolerate this famine that’s going on.”

After that, “To have the strength and the resilience to survive the journey — oftentimes on foot, or hard travels over ocean and boat. And then to have the survival skill to land in a new land with nothing, and somehow find a way. That’s our collective DNA.”

More Information

If you go

“The New Colossus”

Where: Proctors, 432 State St., Schenectady

When: 8 p.m. Friday and 2 p.m. Saturday

Tickets: $25

Info: proctors.org; 518-346-6204

Read More

Robbins’ own American storyline goes back to around 1660, give or take, when John Robbins arrived from England and settled in Massachusetts. He died in 1680. A family Bible passed down for generations tracks the genealogy, its front page thick with history. “My mother’s side had some Irish in it,” he adds. “They came up through Mississippi, Tennessee, Missouri, but then moved out West.”

Both sides landed in California, where his parents met. The actor was born there but grew up in New York City, where his dad — Gil Robbins of the Highwaymen — pursued his career in folk music. Robbins attended SUNY Plattsburgh for two years, becoming “pretty good” at broomball before moving back West, establishing residency and attending UCLA.

Western-state progressivism is in his genes, he says. He talks about this, talks about gratitude and humility, talks about the privilege of being onstage and learning from audiences, talks about his theater work in prisons, talks about the joy in seeing former gang members overcome their former hatreds to hug and make art together. “So yes,” he says. “I do have hope.”

With Tim Robbins on the phone, it has to be asked. What about “Shawshank”? Why, after 26 years, is a contemplative film about inmates so universally loved?

“I’ve been curious about that,” he says. This time, there’s no short answer. “One is that there’s very few movies made that are about friendship, about genuine friendship, between two men. But I also think there’s a theme of redemption in it — and the idea that we all, to some degree, metaphorically build prisons for ourselves in our lives, and some live in those prisons for years. And whether it’s a bad relationship or a sh—y job, for some reason we say, ‘I don’t deserve more than this.'”

The film’s message gives us an answer to all that, he says: We can have our “Shawshank” moments of hope and reclamation. We can walk away and find our spots on the beach.

Has he found his?

The actor pauses a bit before answering. “Yes. Yes,” he says, adding: “That’s an entirely different conversation. … but the short answer has been in realizing that success has to do with a lot more than finance and fame.”

Then, as ever, the short answer turns into a long one.

“One of the things I learned in prison” — meaning his work with inmates — “was something that my grandmother had to teach me, and I might not have learned too well. Which is that real generosity doesn’t have to be acknowledged … and that you’ll never understand how to give love until you learn how to receive love. And that,” he says, “the spirit of love is out there.”

abiancolli@timesunion.com • 518-454-5439 • @AmyBiancolli