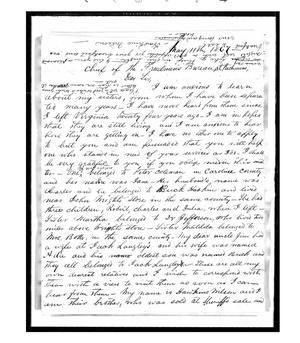

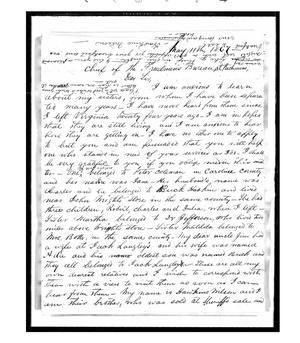

Galveston, Texas. May 11, 1867

Dear Sir,

I am anxious to learn about my sisters, from whom I have been separated many years. I have heard from them since I left Virginia twenty four years ago. I am in hopes that they are still living and I am anxious to hear how they are getting on. I have no other one to apply to but you and am persuaded that you will help who stands in need of your services as I do. I shall be very grateful to you if you oblige me in this matter.

-Excerpt from Wilson’s letter to the Freedmen’s Bureau

Wilson’s words moved actor and comedian Anthony Anderson, who voiced the letters

in “A Dream Delivered: The Lost Letters of Hawkins Wilson,” a documentary centered

around the story.

“Opportunities like these allow me — and others — to learn by learning more Black stories, about the importance of telling all Black stories with greater fullness,” said Anderson, who stars in “Blackish” and “Law & Order.”

Juneteenth brings attention to the somber reality faced by the formerly enslaved — men,

women and children sold off and separated from loved ones. Following the Civil War, Wilson was one of thousands who returned to places from which he had been sold, placed advertisements in newspapers or wrote letters to the Freedmen’s Bureau to enlist the government’s assistance.

Most families, such as Wilson’s, were never reunited.

Now, 155 years later, Ancestry has revealed how descendants can connect their

roots through a digitized Freedmen’s Bureau collection of 3.5 million records. The revelation is the corner stone of the documentary focused on Wilson’s story.

Anderson partnered with Henry Louis Gates Jr., an American literary critic, professor

and historian, as well as director Rashidi Harper, who is known for a dynamic, visual

style that creates visceral depictions of life. Anderson described the emotional roller coaster ride of watching descendants of Wilson discover their lineage complete, honest and authentic Black storytelling.

Grief and anger.

Hurt and pain.

Awareness and inspiration.

“One of my missions as a would-be genealogist is to show that Black ancestry is similar to (white ancestry) in America,” Gates said.

“We all have roots. “The people who sought to enslave and rob (Black people of their) humanity attempted to remove our family lineages. As Frederick Douglass famously wrote in his second autobiography, ‘From Bondage to Freedom,’ ‘genealogical trees did not grow in slavery.'”

Wilson searching for his sisters

One of my sisters belonged to Peter Coleman in Caroline County and her name was Jane. Her husband’s name was Charles and he belonged to Buck Haskin and lived near John Wright’s store in the same county. She had three children, Robert, Charles and Julia, when I left.

Sister Martha belonged to Dr. Jefferson, who lived two miles above Wright’s store. Sister Matilda belonged to Mrs. Botts, in the same county. My dear uncle Jim had a wife at Jack Langley’s and his wife was named Adie and his oldest son was named Buck and they all belonged to Jack Langley.

These are all my own dearest relatives and I wish to correspond with them with a v view to visit them as soon as I can hear from them – My name is Hawkins Wilson and I am their brother, who was sold at Sherriff’s sale and used to belong to Jackson Talley and was bought by M. Wright, Boydtown C.H.

You will please send the enclosed letter to my sister Jane, or some of her family, if she is dead.

In the film, the mother-and-daughter tandem of Marie and Kelly Wilson discovered some of their ancestor’s background and life experiences, including that he was an ordained minister, same as Marie. It’s all part of an effort to allow Black people to connect present and future to past, a source of pride often missing in African American family trees.

“For many Black Americans, they believe their lineages were lost to time, never recorded at all or saved via the recounting of oral traditions,” said Anderson, a six-time NAACP Image Award winner.

“When family members die, younger family members often forget or confuse parts of those traditions, which makes maintaining our legacies difficult. Having access to this information, online, is wonderful because it lets us cut and paste in the names and places we know, and this digital database can do the rest of the work of finding out who preceded us, and where we originated.”

How the Wilsons’ experience moved Anderson

Anderson felt so strongly about the Wilson family, and how the experience motivated him to further his own story, he made sure his son, Nathan, 22, was on the film set.

“I needed him here with me so that he understands the value of maintaining the histories of Black families,” Anderson said. “As far as our own family’s record being remembered two, three or four generations down the line, it’s up to him to make sure that the work I’m doing continues.”

In 2012, Anderson appeared on Gates’ “Finding Your Roots,” a television show that uses traditional genealogical research (written records) and genetics (DNA testing) to discover the family history of famous Americans. Anderson learned he was the descendant of the Bubi people of Bioko Island (Equatorial Guinea) and Cameroon’s Tikar, Hausa and Fulani people.

Since learning about his lineage, Anderson has visited Africa five times. During a trip to Ghana, he wore a purposeful T-shirt while visiting castles where enslaved Africans were once held as prisoners; placed on boats, never to return:

‘I Am My Ancestors’ Wildest Dreams.’

He proudly returned.

Visit Ancestry.com/blackhistory to watch “A Dream Delivered: The Lost Letters of Hawkins Wilson.” The film will also be available on Paramount+, Pluto TV, CBS News channel and on demand, or the CBS News YouTube channel starting Sunday.

Marcus K. Dowling writes about country music in Nashville. He can be reached at mdowling@tennessean.com. Follow him on Twitter @marcuskdowling.