By Aswad Walker | Defender Network | Word In Black

This post was originally published on Defender Network

(WIB) – Over the past few years, there has been an explosion in the number of Black people seeking to find their roots. Some attribute the growth in genealogy activity to the popularity of the PBS series “Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates Jr.”

Another facilitator of Black interest in tracing their ancestors was the digitization of over 3.5 million documents of Freedman’s Bureau records, i.e., information about Black communities in the United States between 1846 and 1878. This is critical because prior to 1870, U.S. Census records did not include the names of the enslaved, choosing rather to list them under the names of their enslavers, or doing something more dehumanizing — merely referring to them as numbers.

Researchers refer to 1870 as the “brick wall,” posing an obstruction to finding out the family history of most Black families because of the lack of information from 1619 to 1870, roughly 250 years.

Amber Jackson is just one of many Blacks nationally who are reaping the benefits of the family search. Jackson told NBC News that she knew little about the history of her family, and thus felt disconnected from who she was. However, by discovering her bloodlines, Jackson experienced a fuller sense of self.

Several Houston-area residents have experienced similar breakthroughs.

“Researching my ancestry is my favorite hobby,” said Tara Jones, adding that AncestryDNA and 23&me were helpful to her search. “I found out my cousin was part of ‘The Stockade Girls’ of Leesburg, Ga. Their story was told on PBS and is archived at the African American Museum in The District.”

And the confidence boost that Jackson mentioned is real. Just ask Danyahel Norris.

“I’ve done genealogy research, both through records and via DNA, and found ancestors born in Virginia as early as 1688,” said Norris. “After that, I’ve been wishing an MF would question if I’m a ‘real American.’ My people have been here at least a century before we were even a country.”

Not all discoveries have been pleasant, however.

“The painful history of the Wilmington Massacre of 1898 is the beginning of the unraveling of my post-Reconstruction family history,” said Dr. Abdul (Robert) Muhammad.

Yet, through the pain have come discoveries those doing the research describe as priceless.

“My cousin is Barbara Jordan and our family history is well-preserved thanks to Bessie Fletcher,” said Vannessa Wade. “We have been able to go back to 200 years of history, including a freed cousin that opened a diner in the Orange, Texas area.”

Shannette Prince, owner of the local business with a global impact, Africa on My Back, is one of many who have been able to see documents listing their ancestors as enslaved.

“My uncle Lloyd has done the research on our family and has marriage certificates, and the documents used that showed family members were ‘sold,’” said Prince.

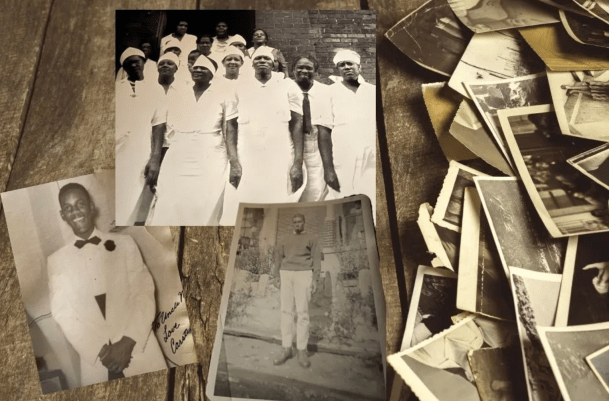

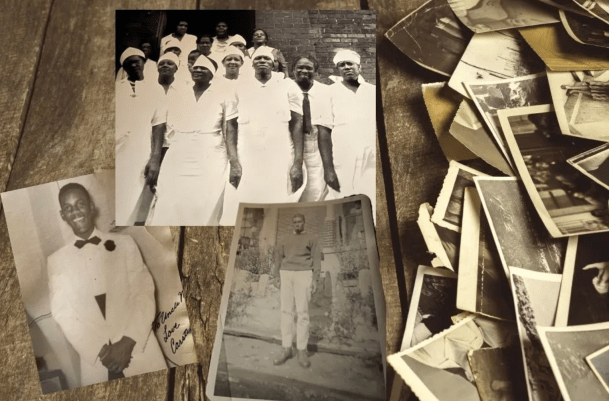

Periodically, the Defender will spotlight a different family tree history shared with us by our faithful, and growing, readership. This month, the spotlight shines upon Tracie Jae, a native Houstonian, mother, and racial conflict mediator, and the journey she’s taken to learn more about her people.

Genealogy Journey: Tracie Jae

When the Defender put out the call for Black people to share stories of their genealogy journeys, the expectation was that we would get a handful of responses, meaning enough to write one good article. To our surprise, we received a tidal wave of responses, prompting us to commit to creating a Black People and Genealogy series.

In the first of our monthly series, Houstonian Tracie Jae talks about her journey.

DEFENDER: What prompted you to start researching your family history?

TRACIE JAE: When my middle daughter graduated from high school, she wanted to go to school in Oklahoma. She wanted to go to OU. She did attend, as an out-of-state student without any notable money for school. And like most Black people in America, we’ve lived under the assumption that there’s some Indian in our blood (air quotes). And there were financial benefits to students in Oklahoma who had Native American heritage. So, I originally started in genealogy research to see if we could prove that for my daughter. We never found it. It’s not there. That was the start. Now, that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist. Because one of the things I’m learning about this genealogy journey and about particularly Black people in America and our sort of interesting classifications is that the census people record you, how they see you. And if you are not directly associated with a tribal community, it doesn’t matter if you happen to be Native American or not. If you are in a community of Black people, you are classified as Black for the matter of the census.

DEFENDER: What’s been the most rewarding part of your genealogy journey?

JAE: There’s actually been a couple of things that were, I guess you would say rewarding. One, I’m able to trace my family on both sides now, back at least five or six generations, which is not always true of Black people in America. And my second great grandfather on my father’s side (George Rivers), so, my paternal grandfather’s paternal grandfather, was born enslaved in Texas. And his narrative is recorded in the Texas slave narratives that was done in 1935. So, I was able to read about him in his words.

DEFENDER: What about the challenging part?

JAE: Just like most Black people trying to research, eventually you reach a stopping point where there is no history. For instance, Molly, who was married to George, lived to be about 100 years old in Texas. There’s a newspaper article about her. I understand the person who was her father was also the plantation owner where she was born. But there’s no record of her mother. There’s a record of her father, a white man with a white family and some other children, but there’s no record of her mother. So, the history of Molly stops there. That’s one of the challenges. The other is an emotional challenge. I’m doing most of my research using Ancestry.com. When Ancestry.com finds somebody that’s connected to you by DNA, they send you a message. “Hey, there’s a hint on your family tree.” Often those hints are attached to the DeBlanc family, which was Molly’s father. So, I get these census things, pictures, etc. that are of the DeBlancs and their white offspring, and all the things that they did in the world as free people. But they don’t really feel like family to me. It’s biology, Its DNA. But these people don’t feel like family.

DEFENDER: What are some of the discoveries that stand out the most?

JAE: My family is primarily from Texas. The Anahuac, Double Bayou area. I knew that as a child growing up, because we would go back there for family reunions and that kind of stuff. At least on my father’s side of the family. My mother’s side of the family is also not far from that area, Liberty County, Dayton. So, same part of the state. It’s interesting to me that the places that the enslaved ancestors that I’ve been able to find, that the places where they settled were not all that far from where they originated. From the places of their birth. Sometimes you read about people who, like during the great migration, lots of Black families left the south and went to places west and north. That’s not my family’s story. My family is Texan. This is where we originate and this is where we stayed.

DEFENDER: Any advice for someone out there who is thinking about taking up their own genealogy journey?

JAE: Absolutely do it. Sometimes, we are afraid of what we might find. But do it. The other thing is, don’t try to do all of it at one time. There’s so much to discover, so much to learn. Start with what you have immediate access to. What do you know about your parents? What do you know about your grandparents, perhaps your great-grandparents? If you happen to be in Houston, the Houston Genealogy Library, the Clayton Branch Library is an amazing resource. If you have any pieces of information and you take it to that library, they will help you begin your search there.

DEFENDER: What did your discovery tell you about yourself? Did you learn anything about you by learning about your family?

JAE: There’s some things that seem trivial maybe. But one of them is that, George was an itinerate pastor in the Methodist church. So, a lay pastor in common terms. And my father’s side of the family has been Methodist since ever. But I didn’t know that it originated with him. I don’t currently practice a particular denomination or even a particular faith for that matter. But, for most of my adult life, up until this point, I did belong to some sort of Methodist situation. The other thing, it may just be coincidence. But I don’t really believe in coincidence deals with the very first thing about earning his first money ever after enslavement. He earned his money by cracking eggs. Somebody paid him money to crack eggs, like a bakery kind of situation. And he bought firecrackers with his first money. And I love firecrackers. Like love, love. I don’t know if that’s why. I don’t know. My sister, on the other hand, hates firecrackers. So, who knows?

DEFENDER: Are you still doing more research on family?

JAE: I’m still looking just because there’s always is more to discover. And fortunately, because of technology, other people are also researching. So, it’s helpful when someone else who happens to be somehow connected to my family is also doing research, because their research feeds mine, and mine feeds theirs. So, I don’t know that I’ll stop. I think it’s been really interesting for me. One of the things that I’ve done as a result of this, I’ve invited other people along on this journey with me, specifically people, because of the work that I do, who would like to reexamine their family history through a racial equity lens. I think it’s one of the things that we fail to do in this new wokeness that America has, is actually sit with and grapple with our own truths about our own families. Which is true of some Black families, but also very true of white families. We have these stories that have been passed down to us as lore and all these great war stories. And we have these heroes in our families, and we never stopped to question how they got to be heroes.

African American Genealogy Sites:

- African Ancestry

- AfriGeneas Genealogy and History Forum

- African American Genealogy: An Online Interactive Guide for Beginners

- Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, Inc.

- Finding Records of Your African American Ancestors, 1870 to the Present

- National Archives and Records Administration: African-American Research

- RootsWeb.com

General Genealogy Sites:

- Ancestry.com

- Cyndi’s List of Genealogy Sites on the Internet

- The DNA Ancestry Project

- FamilySearch

- Genealogy.com

Independent journalism needs YOUR support to survive and thrive. Help us achieve our mission of creating a more informed world by making a one-time or recurring donation today.