ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU) – For the first time in its 96 year history, the International Pacific Halibut Commission will be setting catch limits for halibut this week with the knowledge that the commercial fleet’s catch has been around 90 percent female, a notably higher proportion than previously thought.

“The Commission has long known that the directed commercial Pacific halibut fishery catches mostly female, but we’ve had indications over time that perhaps the fishery is able to capture even more females than we see on a set line survey relative to males,” said Ian Stewart, a quantitative scientist for IPHC.

Stewart works to develop the stock assessment for Pacific halibut, which IPHC commissioners use to set catch limits for the U.S. and Canada. Knowing what percentage of the catch is female is an important factor that could influence how the stock is managed and thus, what restrictions and limitations are put on fishermen. New data from the IPHC shows that the sex ratio of the commercial catch ranged from 81 percent female in some regions of the Gulf of Alaska to 97 percent female in some regions in the Bering Sea.

“For conservation purposes we track female spawning biomass. And in order to understand that we need to know not only how many females are out there, but how many we’re catching in a given year,” Stewart said.

Biologists with IPHC use setline surveys fishing the same gear in the same places with the same bait year after year to estimate trends in the population and collection biological information including size, age and sex.

However, since commercially caught halibut are dressed at sea, meaning the sex organs that identify a fish as male or female are removed, biologists and managers have not been able to tell how closely the commercial catch matches the results from surveys. Until now, information on the sex ratio of the commercial catch was only anecdotal – larger, younger halibut were more likely females while smaller, older fish were more likely males.

The IPHC recognized the importance of knowing the sex-ratio of the commercial catch and developed two methods to collect that information.

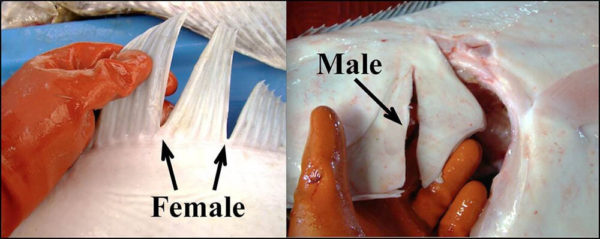

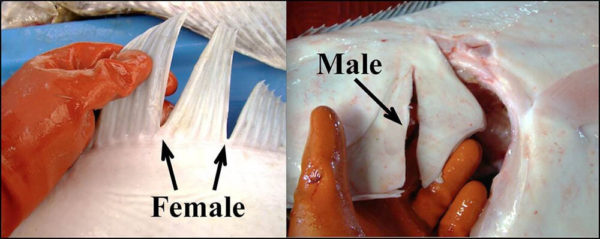

One method involved crews on commercial fishing boats physically marking fish before their gonads were removed. Females were given two parallel cuts in the dorsal fin, while males were given one cut in the gill covering on the white side of the fish.

Simultaneously, IPHC biologists worked with researchers at the University of Washington to develop a way tell the sex of halibut based on DNA collected from small fin clips. The DNA method was used to validate the accuracy of the physical marking, but by 2019 the DNA sampling method proved to be both more accurate and efficient.

“The marking accuracy was fairly high, but at the end of the process, it turned out the technique was actually able to be done in our laboratory at IPHC and the cost was so low that there was really no question that that was the way forward,” said Josep Planas, Branch Manager of the Biological and Ecosystems Branch of the IPHC.

IPHC biologists have analyzed the sex ratio of the 2017 and 2018 catch and this year is the first year the Commission has been able to incorporate that information into its management decisions.

Its impact on the catch limits and allocation won’t be completely known until later this week, but it’s one of many factors that has fisherman bracing for reductions.

“This information has been a key improvement in our understanding in the halibut population dynamics,” Stewart said. “Because we’ve been catching more females in the directed fishery, we need to have more females in the stock to make that work. So what we know understand is that our estimates of population size were a little bit too small without this information. So our estimates are now larger, but in addition, because we are harvesting more females, we also estimate a slightly higher level of fishing intensity being exerted on the stock.”

Since 2016 the Pacific halibut stock has been trending down. Part of the decline is attributed to poor recruitment from 2006 to 2010, meaning that few small fish grew to enter the stock.

“Over the next several years we’re predicting some further decline as those fish work their way through the system,” Stewart said.

Wednesday and Thursday IPHC commissioner, committees and other stakeholders will discuss the status and trends that Stewart, Planas and other scientists presented at the IPHC meetings in Anchorage earlier this week. Friday the commission will decide on the limits that will affect fishermen and other businesses this year.

While new knowledge sex-ratio of the commercial catch should improve science-informed management decisions, there are still several areas that could still be explored to better understand the Pacific halibut stock and how to be conserve it.

“What we’re contemplating is to identify the sex ratio in perhaps fish caught in other fisheries so that we have that sex-ratio information not only from the commercial fishery but other types of fisheries, and then look at the potential environmental effects on the sex ratio. That has been demonstrated in other species and we have no evidence for it in Pacific halibut, but it needs to be studied,” Planas said. “One of the things that would be extremely interesting to do and important would be determine whether the sex ratio in earlier stages – right after birth, after hatching – whether that ratio is actually 50/50 as you would expect, and the difference in the sex ratio we’re finding now, extremely biases towards females, is a fishery related effect.”

Copyright 2020 KTUU. All rights reserved.