All healthy families are alike, a DNA-conscious Leo Tolstoy might have written, and thereby entirely distinct from all those—each miserable “in its own way”—whose bodies or minds are threatened by their very bloodlines. But the Russian author would have been just as mistaken as he was in the famous opening lines of Anna Karenina, where he divided happy families from unhappy ones. As two remarkable books show, there is as much to link as there is to separate the cancer-stricken Gross family in Ami McKay’s recent memoir Daughter of Family G and the Galvins with their six schizophrenic sons, the subjects of Robert Kolker’s forthcoming Hidden Valley Road. Over the course of decades, including times when medical orthodoxy was often intensely hostile to the idea of heritability in the diseases that devastated their families, the two American clans became significant factors in advancing genetic research into cancer and schizophrenia.

Together, their family stories touch on most of the burning issues in contemporary medicine, including the role of genes and their complex interplay with environmental factors in our fates, and the related issues of privacy, family ties and agency—especially when it comes to the question of having children. There is something more, too, running through both books: the terror of choice. How many of us really want to know our likely futures or, even more forebodingly, those of our offspring?

For Indiana-born McKay, now a well-known Nova Scotia-based novelist (The Birth House, The Virgin Cure), learning whether she carried the genetic mutation that had shortened her ancestors’ lives for more than a century was not an easy call. In 2000, after researchers “finally detected the specific mutation that applied to our family through my mom’s DNA, I was one of the earliest to be asked if I wanted to be tested,” she says in an interview. McKay, then 32, was slow to take up the offer because to know would be to have “this thing that sits in the back of your head and doesn’t go away—you could never go back to being the way you were.” Two factors finally sent her to the hospital lab in mid-September 2001, when she was acutely aware of headlines proclaiming America’s “new normal” in the aftermath of 9/11. One reason to accept her own new normal was “my mom saying, ‘Look, you know we’ve gone down this path for generations—think about the benefits when doctors can no longer tell you that maybe you only have the flu or that you don’t really need a colonoscopy at such a young age.’ ” That, and the fact McKay already had two sons. The mutation was known to never reappear once the genetic line of transmission was broken. If McKay was clear, so were her boys. If she was not, “I had to know for their sake as well as mine.”

What McKay went to find out was whether she had any of the five genetic mutations associated with Lynch syndrome, specifically the one on the MSH2 gene that had ravaged her most direct ancestors and closest relatives. The mutation “predisposes” a person, early in life, to at least 13 kinds of cancer, from colon to ovarian to brain—it brings an 85 per cent chance of colon cancer with an average onset at the age of 49. McKay’s uncle was diagnosed with cancer at 26, her grandmother at 50, her mother at 58. The syndrome is named after physician Henry Lynch, known as “the father of cancer genetics,” who picked up the barely flickering torch of cancer syndrome studies from a pioneering pathologist of the early 20th century, Aldred Warthin. But Warthin’s concept and supporting data came from his seamstress, Pauline Gross—McKay’s great-great aunt—who mentioned to him in 1895 that she expected to die young, like so many in her family. (She did, at 46, from cancer.) Thanks to the detailed family chart Pauline Gross provided to Warthin, the list of known Gross victims dates back to 1856. “We are,” McKay writes, “the longest and most detailed cancer genealogy in the world.” For many years, that genealogy was possibly the greatest single factor in keeping alive the notion of heredity in cancer research.

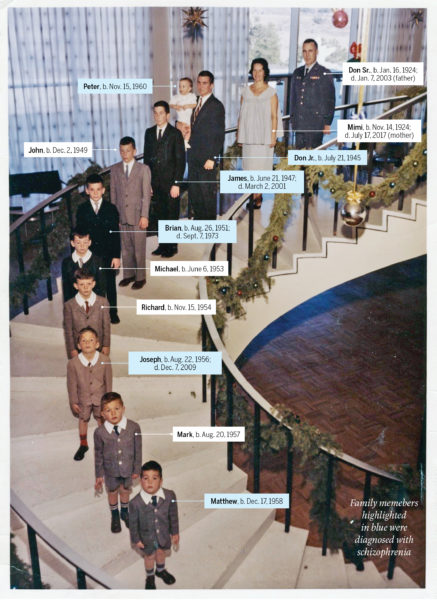

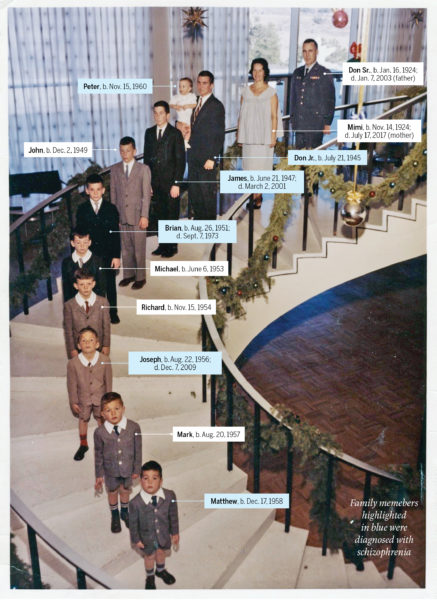

The health records of the Galvins do not stretch as far back as the Grosses’, but their family genetics played an even more pivotal research role in an era when mental health professionals were leaning hard into an understanding of schizophrenia as a psychological and not physical disease. The Galvin family, which eventually settled in Colorado Springs, Colo., began expanding in 1945, when U.S. Air Force officer Don Sr. and Mimi had their first child, Don Jr. It didn’t stop until 1965, a year after the baby boom itself: 10 boys, followed by two girls.

READ: Why understanding the biology of our minds could cure autism and schizophrenia

Don Jr., a good athlete and average student, who was no trouble at all to his parents—they ignored the severe beatings he imposed on his younger brothers while growing up—had his first psychotic break before his last sibling was born. His illness became worse at college, and he was soon back in the parental home, separated from his wife. Meanwhile, brother No. 2, James, who also married very young, began hearing voices and attacking his wife. After he had seemingly recovered, the youngest children were often sent to stay with him when Don Jr. made their lives too chaotic or frightening. James began to sexually abuse his sisters, who, as they later revealed, had been somewhat deadened to abuse because brother No. 4, Brian, had already molested them. In 1973, Brian, 22, prescribed antipsychotic drugs, killed his girlfriend and himself. Two years later, 15-year-old Peter, brother No. 10, had a psychotic break shortly after watching his father have a stroke before his eyes; in 1976, it was the turn of Matt, 17, brother No. 9. By late 1978, there were three Galvin boys in different wards of the same state mental hospital.

The last son to be diagnosed, Joe, brother No. 7, had troubled Peter’s doctors years before while visiting his hospitalized siblings, but he seemed—if only relatively—fine to his family. But, after a series of personal losses, he too began being overwhelmed by hallucinations in 1982 at age 25. Joe later told his mother that a family friend, a Catholic priest to whom Don Sr. and Mimi had often entrusted their boys, had molested them, while Mimi revealed to her adult daughters—after they had confronted her about sending them to James—that she too had been sexually abused as a child, by her stepfather.

In short, the Galvin household offered a horrifically rich mine of potential evidence for any theory of schizophrenia’s causes. And it did so at a time when psychiatry’s nature vs. nurture battle raged on, with many experts still holding to the “schizophrenogenic mother” explanation. That thesis, articulated by the influential German-American psychiatrist Frieda Fromm-Reichmann in 1948, tormented mid-century parents by blaming the disease on “severe early warp and rejection” in infancy and childhood, “as a rule, mainly from a schizophrenogenic mother.” It didn’t help that Mimi—a perfectionist averse to praising her children and secretly troubled by her own trauma—fit the (false) mother-as-bogeyman profile to a T. But if Mimi herself and the vast set of triggers that might have influenced her sons’ individual psychoses interested some psychiatrists, the basic Galvin arithmetic—six boys in one family—captured the attention of researchers seeking a physical cause. By the mid-1980s they had collected blood samples from the Galvins, which soon—unbeknownst to the family—became part of numerous studies.

It was 2016 before the right test offered a breakthrough. Researchers worked with the DNA of only nine families, all of which had to have at least three individuals with schizophrenia and three without. The goal was to find a common genetic mutation, even if it was common only to a particular family, because that abnormality could indicate an overall biochemical pathway to schizophrenia. The study found it in all seven Galvin brothers who had provided blood (two had refused), in the SHANK2 gene, which encodes the proteins that help brain synapses transmit signals. It’s not a smoking-gun cause-of-schizophrenia gene, but it does offer the potential pathway the researchers sought, even as it raises this question: why, when it’s likely all the siblings have that mutation, did some develop serious mental illness and others did not?

READ: What do you do when your wife starts talking to the devil?

In November 2016, after researchers had told the Galvin daughters—their main points of contact with the family—about what they had been doing with the family blood for decades and the SHANK2 findings, Margaret Galvin organized what she called “a blood-drawing party” for non-afflicted family members. These would provide control samples for further research. “Should’ve been on Halloween,” she joked to author Kolker. Some invitees came, those ready to acknowledge their genetic heritage, and some did not.

The family gatherings, the absent relatives and the fortifying humour are all ties that link the Grosses and the Galvins. These are familiar notes to McKay, who describes her “family reunions” in terms of everyday organizing: “I bring the potato salad, you bring the pecan pie, we talk about cancer.” As for those who fear advance knowledge of the future, McKay’s empathy can be interspersed with anger if children are involved. Likewise, the Galvin daughters investigated the chances of passing their brothers’ health onto their own children before they became pregnant, and watched those kids like hawks for any indication that early intervention was needed.

McKay still feels the same about knowing the truth for the sake of her children even though her own news did not turn out well: she has the mutation, and so too do both her sons. What matters now, she says, is to draw the key lesson: “Do things now, don’t wait—and don’t let this thing define your life.”

This article appears in print in the March 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Betrayed by their genes.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.