When humans began to farm and live with their livestock, they evolved a more virulent form of salmonella.

Annette Günzel

Pity the pig. We have blamed it for giving us swine flu, a porcine coronavirus in 2012, and—in some ancient hovel—salmonella, which causes gut distress as well as typhoid fever. Now, though, it seems humans got salmonella first, thousands of years ago, and might have passed it to pigs.

A new study suggests early farmers in Eurasia brought a more deadly form of salmonella on themselves when they switched from a nomadic lifestyle of hunting and gathering to farming. By settling down in close quarters with domestic animals and their waste, they gave Salmonella enterica, which was lurking in an unknown animal host, easy access to the human gut where it adapted to humans. Pigs picked up the pathogen later, perhaps from people or another animal.

Researchers have long thought that the transition from foraging to agriculture made humans sicker. By relying on a few crops and domestic animals, early farmers ate a less varied and healthy diet than hunter-gatherers. They also lived closer to human and animal poop where pathogens persist. But few infectious diseases leave marks on skeletons, so these pathogens have been hard to detect in fossils.

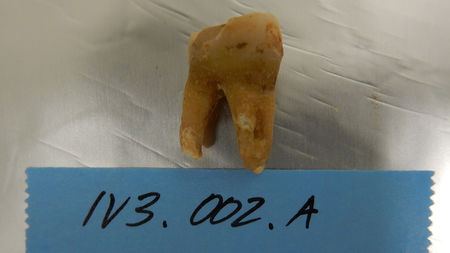

In a technological breakthrough, a team led by population geneticists Felix Key and Johannes Krause and bacterial genomicist Alexander Herbig at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History developed a method called HOPS for detecting bits of ancient DNA from disease-causing bacteria. Key, now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Herbig, and their team used the method to screen bacterial DNA in the teeth of 2739 humans from sites across Europe, Russia, and Turkey dating back more than 6500 years. From those teeth, they were able to reconstruct eight S. enterica genomes.

This 5500-year-old tooth from a pastoralist in Russia had an early strain of salmonella that infected a wide range of animals.

Wolfgang Haak

When the researchers sorted those genomes into a family tree for salmonella, which has more than 2500 strains, they found that all six S. enterica genomes from ancient farmers and pastoralists fell into one group. But two S. enterica genomes from 6500-year-old foragers in Russia fell into other groups, including one with strains that cause miscarriages in horses and sheep. The strains infecting the farmers, who lived 5500 to 1600 years ago, include the progenitor of paratyphi C, a strain that causes a deadly form of enteric fever similar to typhoid fever today.

The researchers do not know which animal host gave it to humans initially, but it probably wasn’t pigs—they carry a closely related strain that arose only 4000 years ago, according to molecular dating of the Salmonella family tree, researchers report today in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

The ancient progenitor strains of paratyphi C had not yet adapted specifically to humans: The pathogens infected a number of animals and lacked genes that cause the typhoidlike fever. This suggests humans initially got a milder form of a disease that also infected their livestock.

Anthropological geneticist Anne Stone at Arizona State University, Tempe, hopes that the team can extract more S. enterica samples from foragers. But the new study sheds light on how bacterial pathogens shift hosts, Stone says. It may also help researchers learn more about when and why pathogens are likely to jump from another species into humans—a timely lesson given the current coronavirus outbreak, she says.