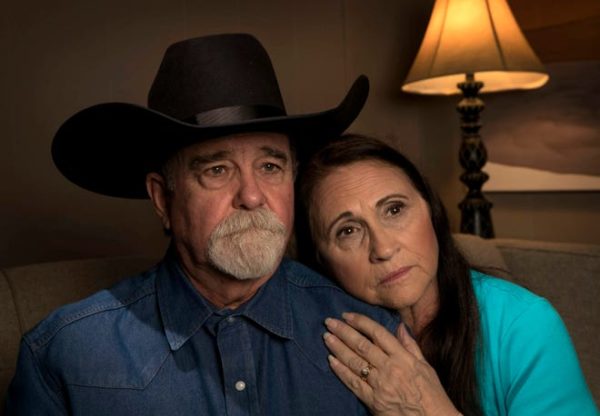

![Bob and Pam Ayers, photographed in Dripping Springs on Wednesday January 15, 2020, are the parents of Amy Ayers, who was murdered in an Austin yogurt shop in 1991. [JAY JANNER/AMERICAN-STATESMAN]](http://geogen.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/fbi-could-hold-the-key-to-a-notorious-texas-cold-case-but-the-info-isnt-being-released-usa-today.jpg)

AUSTIN — The FBI could hold the key to solving one of the most notorious cold cases in Texas history, but the federal agency won’t release the information because of privacy concerns.

Its stance has frustrated investigators, devastated family members and thrust Austin into the spotlight of a growing national debate over the novel use of what some call family-tree forensics.

“That’s all we’ve ever done is ask for help,” says Bob Ayers, whose daughter, 13-year-old Amy, was among those killed. “And now that we’ve found something, we can’t get it.”

At issue is a single strand of DNA collected from a victim in the brutal 1991 slaying of four teenage girls at an Austin yogurt shop. Not a complete sample, the DNA can’t identify a single suspect but could point to that person’s male lineage.

Austin police in 2017 matched the sample to one the FBI uploaded into a public research database operated by the University of Central Florida.

Thus began a years-long battle pitting Austin investigators and their desire to close a decades-old case against the FBI and its concern about unconstitutional overreach.

Some law enforcement officials argue that using partial DNA could help them identify suspects in hard-to-solve cases. But skeptics argue that the practice unfairly casts aspersions on large groups of family members who are likely uninvolved in crime.

For its part, the FBI said it can share DNA in an anonymized format — as was the case for the university database — but that federal law prohibits such samples to be traced to individuals.

The agency also believes that the number of men sharing the same male-only genetic profile could be in the thousands and that officials in Austin are overstating its significance.

Male-only profiles, called Y-STR, the type of DNA in the yogurt shop investigation, have been used to solve several high-profile cases across the country.

Among the first was the case of Albert DeSalvo, who recanted his confessions to being the Boston Strangler in the 1960s and 1970s. He was killed in prison years before the use of DNA in criminal forensics. Decades later, detectives matched his Y-STR found on a victim with that of his nephew, confirming DeSalvo was the killer.

Advocates of family DNA say police are merely using the latest available science to solve cases that are sometimes decades old, involve serial offenders and when other investigative strategies have proven fruitless. They say the technique can provide fresh leads.

But opponents fear the technique is dangerously close to a law enforcement overreach. They fear investigators are outpacing the law in ways that could violate Constitutional protections against seizure and could raise an alarming array of privacy questions.

“This is very volatile information we’re dealing with,” said Erin Murphy, a law professor at New York University who specializes in forensics in criminal justice.

Hopes dashed

Reluctance by the FBI to provide forensic information has contributed to a nearly three-year standoff between federal officials and Travis County prosecutors in the yogurt shop investigation.

In December 1991, four girls — 13-year-old Amy Ayers, 17-year-old Eliza Thomas, 17-year-old Jennifer Harbison and her 15-year-old sister Sarah — were found dead inside the I Can’t Believe It’s Yogurt store in North Austin, which had been robbed and set on fire.

The blaze left investigators with little forensic evidence. But they had been able to get a DNA sample from Ayers. For years, experts were unable to develop a complete profile from the sample. But as scientific advancements allowed them to tease out male strands, investigators grew hopeful.

A decade ago, scientists at a private lab in Virginia identified a male strand of DNA from Ayers’ body. Prosecutors worked for years to find a match, including with one of four suspects in the case, only to be met with repeated failures and disappointment.

The inability to find a match, and the fact that the profile did not implicate any of the four suspects, played a major role in prosecutors’ decision to not retry two defendants in 2009 after courts overturned their convictions. Cases against two other men charged with capital murder were dismissed.

But in 2017, an Austin police detective entered the male DNA profile into a public University of Central Florida research database and found a match. Investigators soon learned that the matching sample was uploaded by the FBI for a population study, and local authorities began pursuing more information from the national lab in Washington.

The FBI has since repeatedly denied their efforts to get information such as how and where the sample was obtained, telling police and prosecutors that they are not legally allowed because the Florida study was anonymous.

According to the agency, the FBI is legally allowed to provide anonymous data for population statistics calculations, but the information can’t be used to trace an individual.

In a statement, the FBI said: “The FBI did not perform forensic DNA testing in this case and cannot speak to this case.”

Investigators and victims’ families say they feel they are being denied information that could further the investigation, if not lead to the killer or killers.

The FBI has long discouraged aspects of family tree forensics for an array of reasons, declaring on its website “routine familial searching is not recommended at this time” and that the science is not used at the national level.

Yet several states have either adopted laws to specifically permit familial searching or, like Texas, have no laws prohibiting it. That has allowed agencies nationwide to develop a patchwork of procedures permitting it.

According to its policy, the Texas Department of Public Safety will use the technique in cases in which it receives a joint request from the district attorney and the investigating law enforcement agency and only in cases involving an “unsolved homicide, sexual assault, or any other crime with significant public safety concerns.”

Experts first began extracting male chromosomes from DNA samples — even those in which they were unable to develop a fully identifiable profile to match one person — in the early 1990s. But according to a 2017 article in The Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law on the topic, its use was not introduced in the United States until about a decade later.

Since then, law enforcement officials cite cases similar to the Boston Strangler in which they say the technique helped them solve high-profile cold cases. In those instances, however, investigators were not relying upon information provided by the FBI, and DNA information came from other sources.

In 2008, Los Angeles police used familial searching to identify a man who killed at least 10 young women from 1985 to 2007.

The use of traditional DNA produced no results when compared against the state’s forensic database. But when they uploaded only the male-specific strand of DNA into the database years later, investigators found a match with a convict who had been in prison. That convict’s father turned out to be the killer.

“It’s evidence that takes you somewhere, even to a limited degree,” said Rock Harmon, a retired senior deputy district attorney in Alameda County, Calif., who consults with law enforcement nationally on cold cases and DNA evidence. “But it still takes you somewhere and is evidence that should be pursued. Family searching is a very focused process, and if you end up, ‘It is one of these brothers,’ then you investigate.”

Wider implications

Others have joined the FBI in its stance that lawmakers and the courts should weigh in on the procedure before it becomes commonplace.

Some jurisdictions, including Maryland and Washington, D.C., have banned familial searching, citing the privacy of citizens who are not suspected of committing any crime.

Murphy said the FBI appears to be properly mindful of wider implications of the routine use of familial searching.

“The point is that in a compelling case it is easy to argue that we should duck the rules and that we shouldn’t let the law get in the way of giving closure to people and holding people accountable,” she said. “But when we start making exceptions, we find ourselves in a place with no law.”

She said the agency is cautious to not overstep its ability outlined in the 1994 federal law that created a national DNA index of people convicted of crimes, commonly called the Combined DNA Index System, and allowed the agency to compare their DNA with evidence from crime scenes.

“One way the courts made that work is that we are going to set up a system that is protective of that information, and that just because your brother is a felon doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have any privacy,” Murphy said.

Hank Greely, a law professor at Stanford law school, said the FBI’s reluctance has been constant for at least a decade as familial searching has grown in use among state labs.

“They have made arguments they aren’t legally authorized to do it — arguments that aren’t frivolous but not strong,” he said. “I think they view it as politically dangerous by making people much more antsy about their database…and the political blowback from their expansive use of genetic resources.”

Critics also have argued that familial searching may not provide enough information for law enforcement, possibly wrongfully casting a cloud of suspicion over innocent family members.

Scientists say Y-strands can create large pools of family members that may be in the hundreds or thousands.

In a statement, the FBI said that such male-specific profiles “are not a means of personal identification.”

“This isn’t like we open the envelope and we know who the killer is,” Murphy said. “We open the envelope, and we find out the killer’s last name is Jones.”

The Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law report said that despite some resistance, courts appear increasingly supportive of the practice to track down criminals.

“Like all innovative forensic methods,” the report concluded, “familial searching will face an uphill battle before it can attain commonplace usage.”