See also “Identifying victims using forensic genealogy”

London resident Debbie Kennett’s journey to becoming a highly trusted specialist in the field of genetic forensic genealogy, and later even an honorary research associate at the University College London, was something she did not plan or expect.

She started as a hobbyist who simply wanted to find out more about her unusual maiden name, Cruwyz. She joined the Guild of One-Name Studies, a group of family historians that focuses on researching one specific last name as opposed to particular ancestors of an individual.

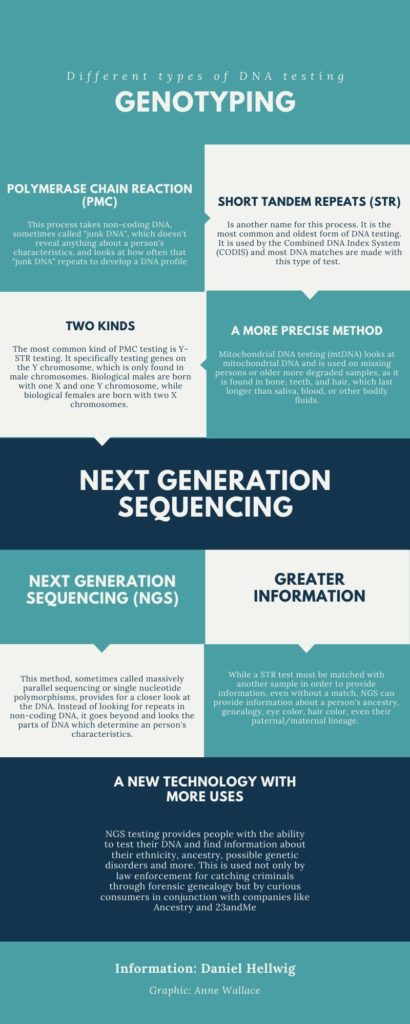

When Kennett joined in 2007, the latest trend was a newer form of DNA testing called next generation sequencing (NGS), or massive parallel sequencing. Rather than just finding matches in DNA like the earlier and more well-known genotyping tests, NGS had the ability to reveal information about an individual’s ancestry, genealogy and even appearance. NGS is the kind of test companies like AncestryDNA or 23andMe run on cheek swabs or saliva submissions to reveal consumer’s ethnic roots along with other genetic information.

Over time, Kennett would take each new and more precise NGS test as it became available to the public. Because of this, she became a recognized name within the genetic genealogy community. She has received so many questions about her work that she created a genetic genealogy Wikipedia page that she continues to manage.

In an effort to combat misinformation about DNA testing, Kennett got involved with the University College London and was granted an honorary position, which eventually led her into forensic genealogy.

“I would define genetic genealogy as the use of genetic tests as a tool for family history research,” Kennett told The Daily Universe in a Skype interview. “Forensic genealogy is just an extension of what we are doing there. The only difference is that instead of providing the DNA sample from a living person, the sample is coming from someone who is deceased or from a crime scene.”

The recent increase in the use of forensic genealogy led most notably to the capture of the Golden State Killer, Joseph James DeAngelo, in 2018. Investigator Paul Holes partnered with genetic genealogist Barbara Rae-Venter and uploaded DNA data taken from crime scenes in the 70s and 80s into an online database called GEDmatch, which stores DNA files and allows people to voluntarily upload their completed NGS test results to find relatives who have also completed DNA tests taken through different companies.

Holes and Rae-Venter used the database to narrow down their suspects, to eventually catch up with DeAngelo and to take a DNA sample from him that matched archived samples from the Golden State Killer. After decades they had finally found him. This particular case, being incredibly high profile, launched forensic genealogy into the spotlight and revealed it’s usefulness. According to Kennett, over 100 cold cases have now been solved using forensic genealogy.

While the tool has proven its efficacy, Kennett shared concerns regarding the process and the steps that justice officials in the United Kingdom are taking to regulate the process. “We have two biometrics commissioners, a forensic science regulator and a biometrics and forensic ethics group,” she said. “They must give approval before we use these methods.”

She contrasted this with the United States’ process that has gone forward largely unregulated until 2019 when the Department of Justice instituted some interim policies regulating forensic genealogy before more permanent regulations can be put into place.

According to Kennett, a significant issue with the process is that there are no official qualifications for genetic or forensic genealogists. “There are all sorts of people who are trying to jump on the bandwagon,” she said. “While we’ve got some people who are doing a great job, there are others who aren’t necessarily following the best methodology and may end up getting things wrong.”

Despite her concerns, Kennett hopes forensic genealogy pushes forward and continues to advance, and hopefully, reaches a point where a universal database could reach virtually anyone via a second or third cousin. “It’s far less invasive than having a basic fingerprint test done or your Facebook accounts searched,” she said. “It’s a case of whether or not the end justifies the means.”

One group taking full advantage of the new technology is the Utah Cold Case Coalition, which is currently building the United States’ first nonprofit forensic lab: Intermountain Forensics. Their vision is simple: the power of forensic DNA should never allow a victim’s justice to go cold.

“Forensic DNA testing has become a staple of criminal investigations in the modern era,” said Daniel Hellwig, the laboratory director and forensic DNA technical leader. Hellwig said many private labs have come into play but their services are costly. Public labs are less expensive but are grossly understaffed, creating a backlog of cases that need testing to progress.

“Cold cases are especially hit hard by this,” said Hellwig. “The older cases can be forgotten and then tend to be very difficult to solve.” Intermountain Forensic plans to combat this by providing additional targeted resources to cases that would fall between the cracks, he said.

Hellwig has been working as a forensic scientist for more than a decade, and in that time he has witnessed how much forensic DNA testing has advanced. “When I first started, a crime scene required a blood stain the size of a nickel to get an accurate result. Now it’s less than the head of a pin,” he said.

Hellwig empathized with the privacy concerns some may have about forensic DNA testing and publicly-accessible DNA databases. “Opt in directives for these databases are a solution that can alleviate some of these concerns,” he said. “But the question remains, if members of my family have allowed databases to have their DNA profiles and thus my genetic profile can be extrapolated, should it be? Do I have a right to genetic privacy in this case?”

Law enforcement cannot use companies like Ancestry, GEDmatch, MyHeritage DNA and 23andMe to access genetic information without the consumer opting in or without a specific court order. Despite this, some companies, like Family Tree DNA, actively collaborate with the FBI.

While Hellwig acknowledged the gray areas, he said he stands in firm support of the use of forensic genealogy. “This is a powerful tool that can revolutionize investigations,” he said, “but with great power comes great responsibility.”