As the year comes to a close, we once again asked our reporters to share the most memorable story they wrote in 2022.

The fifth Knesset election in less than four years, along with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, steered much of our coverage. We reported from Jerusalem and the West Bank, from Doha and Lviv. We analyzed the Israeli political arena, shined a light on challenges faced by Jews in the Diaspora, and pressed the #MeToo conversation forward.

But we also offered readers — and podcast listeners — a respite and reason for optimism, with stories on Israeli citizens and companies making a global impact through technology, innovation and altruism.

We hope those stories will only multiply in 2023.

An honest account of the Ayia Napa affair

Ricky Ben-David

Two years after a British teenager was found guilty of lying about being gang-raped by a group of Israeli youths while on vacation in Cyprus, the Cypriot Supreme Court overturned that ruling in January, bringing some closure to a saga that started as a holiday romance in the summer of 2019 and unfolded as a media circus in three countries.

In Israel, and particularly in the Hebrew press, coverage of the so-called Ayia Napa affair was rife with rumors and falsehoods that were part of a sea of misinformation surrounding the alleged rape and the character of the 19-year-old complainant. Intimate videos of the teen engaging in consensual sex, on a separate night, with one of the Israeli teens circulated widely in Israel, solidifying the idea for many that she had falsely accused the Israeli youths.

I followed the story closely that summer and slowly began reaching out to the complainant’s defense team, the Israeli youths’ lawyer, and a host of activists, experts and journalists while poring over court documents.

A 19-year-old British woman, center, who was found guilty of making up claims she was raped by up to 12 Israelis, arrives at Famagusta District Court in Cyprus for sentencing on January 7, 2020. (AP Photo/Petros Karadjias)

Few recent stories in Israel yielded such a wide gap between the amount of sensationalist media coverage and actual general knowledge of the details. I set out to write the most comprehensive telling of events possible while weaving in heart-rending descriptions by the British teen from the night of the alleged rape, court testimony, expert analysis and details of the general media atmosphere.

Some of it made for difficult reading, especially for victims of sexual assault — feedback I heard over and over again from readers and colleagues. The piece, published in February, makes no definitive assertions on the rape allegations. Unless the Cypriot police reopen the case and conduct a rape investigation — an unlikely event — we’ll never truly know. But people can walk away from the article with more knowledge and context about an ordeal that touched on rape culture, victim-blaming, and single-sided narratives, and likely resulted in life-long trauma.

The long arc: 3 years on, the Cyprus gang rape case begins to bend the other way

—

Why ‘the king’ hasn’t been dethroned

Amy Spiro

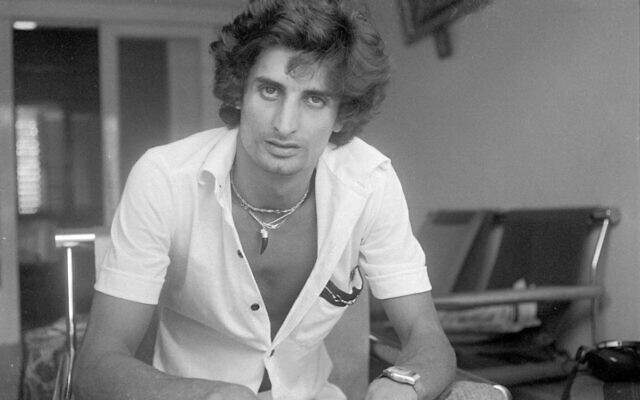

Even though he’s been dead for 35 years, it’s nearly impossible to escape the music of Zohar Argov in Israel. His songs are still played on the radio, performed on TV song contests and featured in constant rotation on DJ sets.

I set out earlier this year to understand why Argov — who was convicted of rape and took his own life behind bars while a separate rape charge was pending — is still known in the mainstream Israeli music world as “the king.”

The journey led me to better comprehend the enormous role Argov, the son of Yemenite immigrants, played in bringing recognition and pride to Mizrahi music in the 1980s as well as the huge impact he had during a career of just five years. It also helped me spotlight the struggle of those activists who have not stopped battling efforts — including by contemporary musicians — to whitewash Argov’s crimes.

Unfit to be ‘the king’: How singer Zohar Argov’s legacy continues to be whitewashed

—

Addiction does not discriminate

Luke Tress

I started looking into a story about the Sackler family, the owners of Purdue Pharma, and its role in the opiate crisis. Soon after I started reporting I realized the more important story was about addiction and overdoses in Jewish communities and the staggering toll across the US.

The crisis seems to have been overshadowed by the pandemic and other news, leaving many unaware of how many people are dying — more than the AIDS epidemic at its peak and more each year than US deaths in the entire Vietnam war.

I was also guilty, like many probably are, of thinking it was less widespread in Jewish communities, but everyone I spoke to said the same thing: addiction doesn’t discriminate.

An activist sets up cardboard gravestones with the names of victims of opioid overdose outside the courthouse where the Purdue Pharma bankruptcy case took place in White Plains, New York, on August 9, 2021. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

This story was important for shedding light on these issues, especially since fentanyl is now making its way into fake pills, becoming the leading cause of death for young people in the US. People should be aware. I’m thankful to those who shared painful stories with me for this article and hope it does some good.

Jewish communities grapple with addiction as fentanyl crisis ravages US

—

Democracy in crisis

David Horovitz

In the course of this year, and especially the past few weeks, I’ve written more articles than ever before that I didn’t want to write or think I’d ever feel moved to write — about the crisis in Israeli democracy and its lurch toward a tyranny of the majority.

I realized more clearly than ever before where the political winds were blowing when I walked through the Muslim Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City in May, in what I referred to as a “triumphalist march by Orthodox-nationalist men.”

“Some of the marchers had circular stickers on their shirts proclaiming ‘Rabbi Kahane was right’ and were distributing stickers hailing the late racist rabbi’s disciple Itamar Ben Gvir, now a Knesset member from the Religious Zionism party,” I noted.

“A poll over the weekend showed [Naftali] Bennett’s Yamina party, now partnered in a unity government with parties from across Israel’s political spectrum, sinking to just five seats were elections held today (from seven in April 2021), and his Religious Zionism party rivals Bezalel Smotrich and Ben Gvir, outspoken opponents of a government reliant on the Arab party Ra’am, rising from six seats last year to eight. Watching the 70,000 Flag Day marchers pass — a far larger number than police had anticipated — those survey figures suggested the underestimating of a trend,” I wrote.

Head of the Religious Zionism Party MK Bezalel Smotrich waves an Israeli flag at Damascus Gate outside Jerusalem’s Old City, during Jerusalem Day celebrations, May 29, 2022. (Olivier Fitoussi/Flash90)

“This was a show of force by a young and fast-growing section of the Israeli electorate for some of whom Bennett is a sellout, [Benjamin] Netanyahu a wimp who tried in vain to appease the terrorists of Hamas by rerouting and then abandoning this march a year ago, and Ben Gvir (ushered into the Knesset in an arrangement brokered by Netanyahu) the real deal.”

Five months later, the November 1 elections indeed confirmed “the underestimating of a trend,” with a vote that I argued a day later marked “the elevation of Jewish Israel above democratic Israel.”

And now Netanyahu, conceding to the extremists, is hatching what I’ve called an “intolerant, alienating, vulnerable Israel.” The coalition agreements he finalized include a commitment to legislation that would permit service providers to refuse service (and potentially doctors to refuse treatments, according to one of its proposers from the Religious Zionism party) on the basis of their “religious beliefs” — i.e., legalized discrimination; to “override” the High Court if and when the justices strike down legislation that breaches Israel’s quasi-constitutional Basic Laws; to amend the Law of Return to make it harder for those who are not halachically Jewish to immigrate, among innumerable contentious clauses.

There is still time to retreat from the democratic abyss. Coalition agreements are not sacrosanct or legally binding. Helming his new government, Netanyahu has the authority to resist his colleagues’ declared agendas even now that he has given them prominent roles and signed off on their proposals.

For Israel’s sake, resist he must.

Through Jerusalem’s Muslim Quarter, a triumphalist march by Orthodox-nationalist men

—

From fringe to mainstream: The rise of Itamar Ben Gvir

Jacob Magid

I know we’re not supposed to say this, but I rather enjoy covering Israeli elections. They provide a break from the US beat I’ve held for the past two years and allow me to return to some of the people and places I reported on as settlements correspondent.

It was in that capacity that I first met Itamar Ben Gvir, a resident of the Jewish settlement in Hebron who worked as an attorney defending far-right activists and Jewish terror suspects. It seemed clear six years ago that he was destined for the national stage, thanks to his charisma and media savvy. But his views and his associates — not to mention his own criminal past — kept widespread acceptance beyond reach.

In four straight elections, his far-right Otzma Yehudit party produced lackluster results, failing to cross the electoral threshold the first three times and only managing to squeak into the Knesset on the fourth try thanks to a Benjamin Netanyahu-orchestrated merger with Bezalel Smotrich’s Religious Zionism party.

MK Itamar Ben Gvir seen during a plenum session in the Knesset on June 20, 2022. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

But whether it was the longtime prime minister’s normalization of Ben Gvir, the self-described Meir Kahane disciple’s claim that he’d softened his views, or an Israeli electorate’s shift further to the right, the Otzma Yehudit leader was no longer viewed as a fringe candidate in this past November’s vote.

As he walked out of his polling station mobbed by media and supporters on November 1, I quipped to him that a lot has changed since he first became head of Otzma Yehudit four years earlier. “You were the only reporter here then,” he replied, smiling.

His joint slate with the similarly hardline Religious Zionism and Noam factions won 14 seats that day, and Ben Gvir will now play a central role in the next government as national security minister.

It took 4 voting rounds to normalize Ben Gvir. By the end of the 5th, he’s a star

—

Wanted: A new Israeli left

Haviv Rettig Gur

No election is an island. Every time voters upset the expectations of campaigns and pundits, they are signaling deeper changes and trends — and sometimes crises and suffering — that the self-appointed interpreters of the people’s will were failing to notice.

In this case, the collapse of the Israeli left in November’s election was a reality everyone but the left seemed to see coming. The left’s political leadership had good reason to stubbornly fail to notice the prevailing trend: It amounts to a stinging indictment of left-wing political structures and elites by their once-loyal rank and file.

Meretz party supporters react as the results of the Israeli elections are announced, in Jerusalem on November 1, 2022. (Flash90)

A new left may arise out of the ashes of the old that might challenge the Israeli right. If we accept the premise that competition is good and lack of competition is corrupting, such a development would be healthy for all sides. But for that to happen, the old, failed left must step aside. On November 1, left-wing voters passed that message to their leadership, mostly by staying home. They did it too resoundingly to ignore.

The Israeli left has lost more than an election

—

If at first you don’t succeed, build, build again

Jeremy Sharon

Illegal settlement outposts — the clusters of rickety buildings put up without authorization by ragtag crews of intensely ideological young men and women on desolate hilltops in the West Bank — are not new.

Numerous such wildcat hamlets exist across the territory. They’re established, razed, and rebuilt every year, frequently accompanied by allegations of violence perpetrated by their settler inhabitants toward neighboring Palestinians.

The story we published on Ramat Migron — destroyed and rebuilt at least four times over the course of August and September — seems especially relevant though, in light of the formation of what has been labeled Israel’s most right-wing government ever.

The young activists at the site said they drew inspiration from early Zionist pioneers and that they would rebuild it “a hundred times over” in order to secure the future of their settlement.

With hardcore settler ideologue Bezalel Smotrich, leader of the Religious Zionism party, set to take control within the new government of two key Defense Ministry agencies that have power over authorizing planning for settlement construction, the future now seems much brighter for Ramat Migron.

Raze, rebuild, repeat: The relentless settlers of Ramat Migron

Israel has a gun problem

Emanuel Fabian

The past year has seen a major uptick in violence in the West Bank. Armed terror group members have repeatedly opened fire on Israeli troops operating in Palestinian cities, Israeli settlements, and civilians on the roads. Meanwhile, the Arab community in Israel has seen record-breaking numbers of murders — a toll of 115 this year and 125 last year — mostly with illegal firearms.

After seeing numerous videos on social media of Palestinians brandishing M16 assault rifles following clashes with the military and the near-daily deadly shootings in the Arab community, I sought an answer to the question — where are all these guns coming from and what are Israel’s security forces doing to seize them?

Police and military officials who spoke to The Times of Israel said the vast majority of the illegal guns cycling through the West Bank and Israel originate from smuggling incidents over the border with Jordan. Indeed, law enforcement officials have repeatedly announced successful seizures of weapons that slipped through the border.

Weapons seized by security forces in the Jordan Valley, after an alleged gun-smuggling attempt over the border with Jordan on October 3, 2022. (Israel Police)

This piece dives into what is spurring these smuggling attempts and how Israeli security forces are beginning to clamp down on them. This past year, almost 500 guns have been seized, and officials estimate they are catching around 80 percent of the guns brought over the border, compared to around 15% several years ago.

Still, it remains to be seen if these efforts will have lasting effects on the currently rampant gun violence.

On porous Jordan border, Israel starts to see success against rampant gun-smuggling

—

Your Holy Sepulchre audio guide

Amanda Borschel-Dan

This April, just before Easter, I was privileged to tour the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem Old City with top archaeologist Prof. Jodi Magness.

Usually a bustling center of Christian life, during the coronavirus epidemic it often stood empty — aside from some excavations and renovations.

We toured the church and its surroundings, seeing parts of the ruins of earlier stages of the church, including an arguably Christian find that predates the Constantine construction in around 330 CE, as well as remains of earlier structures.

“Many scholars think that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre likely is the authentic spot where Jesus was crucified and buried because the tradition is so ancient. But you still have that 300-year gap, which is a leap of faith that archeology cannot cross,” says Magness.

By the end of the tour, we saw what Magness feels is the best evidence that supports the Christian tradition, although, as she emphasized, nothing is unambiguous.

Christian pilgrims hold candles as they gather during the ceremony of the Holy Fire at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Old City of Jerusalem on April 23, 2022. (Olivier Fitoussi/Flash90)

The church today hums again with liturgical music and wafts of incense fill the air.

Magness generously agreed to record our tour as a podcast, so when you’re next in Jerusalem, let her expertise be your audio guide.

What does archaeology say about the location of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre?

—

Israelis reflect on their wet hot American summer

Jessica Steinberg

I joined our podcasting team nearly a year and a half ago, taking over the daily and weekly podcasts while Amanda Borschel-Dan was on maternity leave. It was trial by fire, learning how to produce and host our Daily Briefing.

However, through our weekly Times Will Tell episodes I’ve had the opportunity to take a deeper dive into the stories and people we cover.

One of my favorites was an unexpectedly popular episode we released in August, interviewing two Israeli shlichim — or emissaries — who spent the summer working at Camp Ramah in the Poconos. It’s a place where I also spend time most summers, continuing my Times of Israel work from the Pennsylvania forest, Wi-Fi permitting.

The interview with two Israeli twenty-somethings was eye-opening — for them and I believe for our audience as well. They spoke about the challenges and unexpected joys of their Jewish summer camp experience and about what it’s like getting to know this slice of American Jewish life.

Halleli Busheri (left) and Tair Offir, two ‘shlichim,’ or emissaries, on staff at Camp Ramah in the Poconos during summer 2022 (Courtesy)

Although I have spent so much time in this same place over the last 35 years, it enlightened me as well, and it’s heartening to know that so many of our listeners felt the same way.

Podcast: ‘Just like in the movies,’ say Israeli counselors of US sleepaway camp

—

A Jewish-Roma music virtuoso’s legacy lives on

Yaakov Schwartz

From left: Gyulane Farkas, Istvan Feher, Aron Feher and David Feher at Giero Pub, Budapest, May 16, 2022. (Yaakov Schwartz/Times of Israel)

When I moved to Budapest in late 2017, I stumbled upon a hidden gem: a small family-run basement venue with live Gypsy music each night after 10 p.m. The music is top-notch and had me coming back multiple times a week, usually by myself but sometimes with visiting friends or a local date I was looking to impress.

Over time, I got to know the purveyor, Gizi, a sweet older Roma woman who dotes on her guests like a grandmother and occasionally bickers with the musicians — who happen to be her nephews. It was only recently, though, that she mentioned her Jewish roots. She told me how the Holocaust affected both sides of her family, as well as the story of her father, the pub’s namesake, a half-Jewish, half-Roma double bass virtuoso named Giero.

In Budapest, an underground ‘Gypsy music’ pub plays on Jewish heartstrings

—

It’s a girl!

Sue Surkes

How many people realize that the production of their morning scrambled eggs or sunny sides up costs the lives of seven billion male chicks each year? Across the world, they end up gassed, suffocated or buried alive because the industry regards them as waste.

The Israeli Agricultural Research Organization — Volcani Center decided to address this harrowing phenomenon and earlier this month announced that it had succeeded in producing hens that only produce female chicks — something never done before.

The research team discovered a way to genetically edit the hen’s female chromosomes so that eggs carrying male embryos will stop developing at an early stage and will not hatch.

The so-called Golda hens will be kept at poultry breeding centers, while their offspring will be sold to farmers for the production of unfertilized eggs for human consumption.

In first, Israeli scientists program hens to lay eggs that carry only female chicks

—

Alien crash landing?

Rich Tenorio

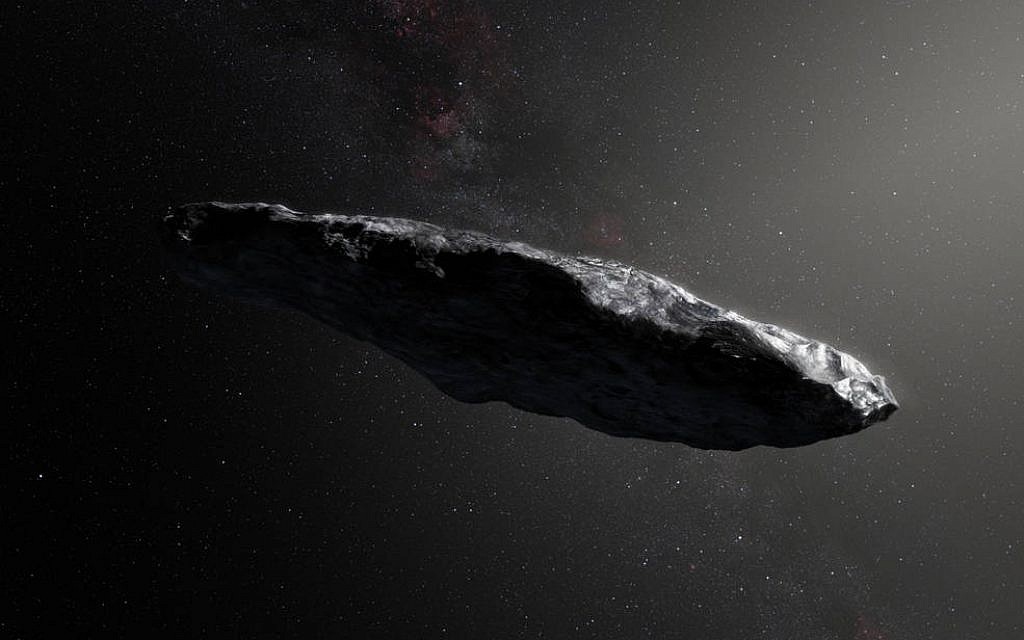

I first interviewed Prof. Avi Loeb, back in the pre-COVID days of 2019. A sabra who was at the time the chair of the Harvard University astronomy department, he shared his claim that a mysterious, pancake-shaped object detected in the sky in 2017 called ‘Oumuamua might be extraterrestrial in origin.

I continued to follow Loeb’s career after he took a sabbatical from Harvard to publish a book on ‘Oumuamua. But I still wasn’t prepared for the news that rocked the science world this spring: In a tweet, the US government backed Loeb’s claim that another object — a meteor that crashed off the New Guinea coast in 2014 — likely originated from beyond our solar system. It was time for another interview.

An illustration of ‘Oumuamua, the first object we’ve ever seen pass through our own solar system that may have interstellar origins. (NASA Goddard Center/CC-SA-2.0)

Loeb has since firmed up his plans to go to New Guinea to search for traces of the 2014 meteor. Suffice it to say I will be keeping an eye on his trip from afar.

Israeli scientist proves his far-out theory on interstellar meteor is down to earth

—

When synagogues double as refugee shelters

Carrie Keller-Lynn

It gave me chills to revisit my story on a Purim megillah reading in Lviv, Ukraine, which took place less than a month after Russian forces invaded the country.

The western city was still grappling with its place in the war in those early days. Lviv had turned into a transit hub for the millions of refugees flooding the country’s borders, and the Turei Zahav community’s synagogue was doubling as a refugee shelter.

Groups of Ukrainian refugees walk along the road between Lviv and Shehyni, in Volytsya, Ukraine, March 5, 2022. (AP Photo/Marc Sanye)

Like much in Lviv in those tense, early days, Purim became more of a commemoration than a celebration. Less than two days after the megillah reading, the city absorbed the first of many Russian missile salvos.

Like many I met in my short time in Ukraine and Poland at the onset of the invasion, the Turei Zahav community wished for a swift end to the war. More than nine months later, none is in sight.

The Book of Esther is read, against the odds, in the ruins of oldest Lviv synagogue

—

Fighting to find Ukraine’s fighters

Lazar Berman

On August 12, during my third trip to wartime Ukraine this year, I sat in Kyiv with three brave women whose loved ones were believed to be held in Russian POW camps – if they were alive at all.

They were desperate to get their stories out in the hope that someone – a foreign government, an international organization – would care enough to at least confirm the locations of their sons, boyfriends and husbands.

One woman, Tatiana, lost her father during the war. Her only son was taken during the surrender at Mariupol, and she knew only that he was in the Olenivka POW camp. Dozens of Ukrainian soldiers were killed during a July 29 blast at the camp, and Tatiana did not know whether her son was among the fallen.

Another woman, Vlada, endured Russian gunfire and 20 checkpoints to escape Mariupol. When she spoke to me, she believed her fiancé Pavel was also being held at Olenivka.

Ukrainian flags are placed in memory of those killed during the war near Maidan Square in central Kyiv, Ukraine, November 11, 2022. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

Those women are among hundreds who have banded together to fight for the release of their loved ones. They spend their waking hours calling, filling out forms, marching, and hoping. “From talking to one another, we started supporting one another,” Yana, 29, told me. “We took matters into our own hands.

“Right now, I’m like steel,” said Yana, whose fiancé surrendered at the Russian-occupied Azovstal steel plant. “Nothing can penetrate me. I’m just trying to go work as much as I can, especially helping the other families.”

Meeting such courageous, determined women, and enabling their stories to reach the world, was a uniquely poignant moment in my journalistic career.

With loved ones in Russian camps, Ukrainian women fight to bring them home

—

How Jewish groups came through for Ukrainians

Judah Ari Gross

Good news is hard to come by in the journalism world. Reporters often look for areas where there’s a problem or where things aren’t working in hope of spurring a solution. That’s important work, but it can also be a bit depressing. That’s why my favorite story of 2022 focuses on where things went right — where people worked together toward a common good.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Jewish and Israeli organizations sprang to action to help refugees immigrate to Israel or settle in Europe and to provide aid to the people who didn’t want to or couldn’t leave their war-torn homeland. It required groups to work in places where they had minimal experience and to coordinate complex rescue and relief operations in the fog of war. Many of the organizations involved were large, heritage institutions not known for their flexibility and speed. And yet, despite these challenges, they worked together shockingly well, adapting to difficult conditions and moving quickly to help as many people as possible.

Holocaust survivors rescued from the war in Ukraine arrive at Ben Gurion airport near Tel Aviv, April 27, 2022. (Tomer Neuberg/Flash90)

I heard about this remarkable cooperation from people on the ground and otherwise involved in the aid operations, and it’s what the OLAM network of Jewish and Israeli aid organizations found when it conducted a survey about the response to the ongoing humanitarian disaster: When Europe saw its largest refugee crisis since World War II, Jewish groups turned up to provide indispensable assistance to those in need.

Survey hails Jewish, Israeli aid groups’ Ukraine war response

—

The Israeli man in the middle

Tal Schneider

Exhausted from Israeli politicians after covering five elections, I’ve found working on stories from “other worlds” to be refreshing and rejuvenating. Earlier this month, I had the opportunity to speak with Mickey Bergman from the Richardson Center for Global Engagement, a nonprofit US organization that specializes in returning Americans imprisoned around the world, about his little-known role in the talks that led to the freeing of WNBA star Britney Griner from Russian jail.

Griner’s family reached out to the Richardson Center last February in light of Bergman’s involvement in the release of former Marine Trevor Reed from Russia in April 2022 and the return of Jewish-American journalist Danny Fenster from Myanmar in November 2021.

A former IDF officer, Bergman recalled how he helped navigate the family through the nightmarish situation before flying out to Moscow for informal talks with Russian officials with whom he’s built ties over his years at the Richardson Center.

WNBA star and two-time Olympic gold medalist Brittney Griner speaks to her lawyers standing in a cage at a courtroom prior to a hearing, in Khimki just outside Moscow, Russia, July 26, 2022. (AP Photo/Alexander Zemlianichenko)

One wouldn’t necessarily expect that a nonprofit could assist governments in such negotiations, let alone replace them altogether. But Bergman’s ability to work just outside the boundaries of government capacity has proven essential in bringing Americans home.

Practicing ‘fringe diplomacy,’ Israeli negotiator secured release of Brittney Griner

—

Chatting up Iranians at the World Cup

Ash Obel

Wandering outside Doha’s Khalifa International Stadium at last month’s World Cup, I had the opportunity to speak face-to-face with Iranian citizens for the first time in my life.

These exchanges exposed me to some of the complexities of being an Iranian in 2022.

Almost all I interviewed were fiercely patriotic and proud to wear the colors of their national team. At the same time, when asked about the protests that have swept through their home country, many interviewees seemed surprisingly eager to express their solidarity with the demonstrators to an Israeli journalist — albeit anonymously.

Iranian soccer fans pose for a selfie prior to the World Cup group B soccer match between England and Iran at the Khalifa International Stadium in Doha, Qatar, November 21, 2022. (AP Photo/Frank Augstein)

The sheer volume and ferocity of dissent made the simmering revolution in Iran feel very real and capable of presenting the regime with a palpable challenge to its authority.

‘I’m talking to an Israeli journalist!’ Giggles and grace from Iranians at World Cup

—

The Kindertransport children’s second parents

Robert Philpot

As the first Ukrainian refugees began arriving in the United Kingdom at the beginning of the year, I coincidentally started work on a piece about a somewhat similar moment 80 years ago: the Kindertransport of 10,000 Jewish children escaping the Nazis to Britain on the eve of World War II.

The stories of the Kindertransport children — and their later contribution to British society — have been recorded and celebrated in the UK for many years. But less is known about the foster families who took them in. That’s now changing thanks to a new project undertaken by historian and Holocaust educator Mike Levy. Funded by the US Holocaust Memorial and Museum, he is interviewing British families who hosted the Kindertransport children. As part of my reporting, I spoke to one of Levy’s interviewees, Ann Chadwick, whose parents took in 5-year-old Suzanne Spitzer.

The Children of the Kindertransport sculpture, outside Liverpool Street Station in London. (John Chase, 2006)

Even in these bleak moments, Chadwick’s recollections provide a welcome reminder of the innate decency of those who held out a hand of rescue to refugees — both eight decades ago and today.

And there’s nothing patronizing or condescending in her retelling of the story. “It was a huge privilege that we had her,” Chadwick said. Her research after Suzie’s death “drew me very closely into the Jewish world” and into Holocaust education work. “It’s added to my life experience and I’m very, very grateful for it,” Chadwick recalled.

When Jewish kids fled Nazis, UK families took them in. Now they share their stories

—

Giving family to those who thought they had none left

Renee Ghert-Zand

The fascinating and poignant story of British octogenarian Jackie Young exemplifies the power of Jewish genetic genealogy. Commercial DNA testing now makes it possible for Holocaust orphans like Young to learn more about their identities and enables survivors to connect with relatives they never knew they had.

Young, who miraculously survived Theresienstadt as a baby and was adopted by a London couple, only discovered his horrible past as a young adult. He searched for information about his biological parents for decades to almost no avail. He recently turned to the BBC program, “DNA Family Secrets” for help. The show’s genealogists were able to confirm that his father was an Ashkenazi Jew, allaying Young’s long-held fear that his dad could have been a Nazi. The show also connected Young with two distant cousins.

Ashkenazi Jewish genetic genealogy experts Jennifer Mendelsohn and Dr. Adina Newman, who recently launched the DNA Reunion Project at the Center for Jewish History in New York, offered to take the research further. Within five days, they were able to determine Young’s biological father’s name and also that he has living relatives on his paternal side in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Israel, and possibly Hungary.

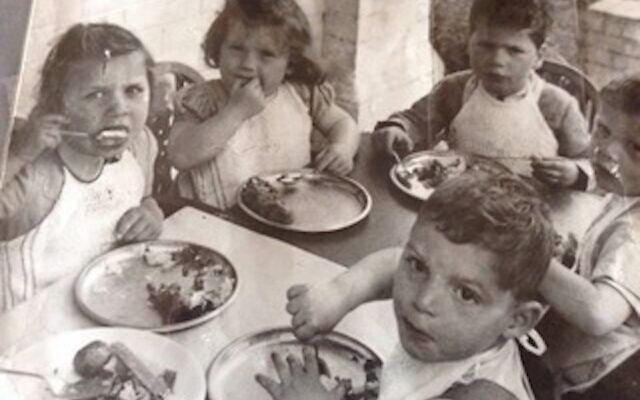

A young Jackie Young (then known as Jona Spiegel), at the head of the table on right, at mealtime at Bulldog’s Bank in Sussex, where he lived during his first year in the UK under the supervision of Anna Freud and sisters Sophie and Gertrude Dann. (Courtesy)

To confirm their findings, Mendelsohn and Newman needed to find a close relative on Young’s biological paternal side to take a DNA test, which proved the genetic match. Bill Kornfein, a retired St. Louis lawyer and Young’s first cousin once removed, agreed to be tested. It was a definitive match. The cousins — who look like they could be brothers — are in regular touch and plan to meet in person soon.

“I’ve been waiting for this news for six decades. I’m not alone anymore,” Young said.

UK man who survived concentration camp as baby finally learns his family’s identity

—

The mental health toll of campus antisemitism

Cathryn Prince

When Micah Gritz first arrived at Tufts University two years ago, he never expected that he would have to hide his Jewish identity just so he could get through a day of classes. But that’s what he said has been his reality — one shared by scores of Jewish students on campuses nationwide.

Speaking with Gritz and dozens of other students for this story, I realized there was a less obvious but equally important facet of this phenomenon: the mental health toll antisemitism takes on students.

I was surprised at how relieved some were to talk about how their experiences impacted their time on campus. It led some to underperform academically and even transfer universities to escape what they described as hostile climates. The US Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights is now investigating several of these universities for not protecting Jewish students or doing enough to address campus antisemitism. While these probes will determine whether the universities violated Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination based on race and religion, they can never give back the sense of trust and security so many of these students have lost.

Illustrative undated photo of antisemitic graffiti on a building near the University of Virginia campus in Charlottesville. (Courtesy of Michaela Brown)

Although this is not a happy story, I feel it’s the most meaningful one I have written this past year. It was a way to humanize an issue I’ve covered for years and, I hope, help people realize that behind every story about an antisemitic incident is a person who will be feeling the effects long after the graffiti is scrubbed clean or the perpetrators are disciplined.

US students report jump in mental scarring from campus antisemitism, but see no end