We don’t often get a glimpse of what 19th-century Americans looked like, let alone those accused of being “vampires.”

Scientists at a forensics company and a military lab have been able to do just that, by creating an image of a man who was likely suspected of being a vampire when he died in rural Connecticut in the 1900s.

John Barber’s remains were discovered in 1990, in a Griswold graveyard that was found by children who were digging around in a gravel quarry. His identity was later revealed using DNA testing in 2019.

Barber’s remains were found at an unmarked grave along with a wooden coffin that had “JB55” etched on it. His skull and limbs were rearranged atop the ribs in a skull-and-crossbones style approximately five years after his initial death, which indicated whoever buried him suspected that he was a vampire.

Further research found that Barber was roughly 55 years old upon the time of his death, and that he most likely died from tuberculosis.

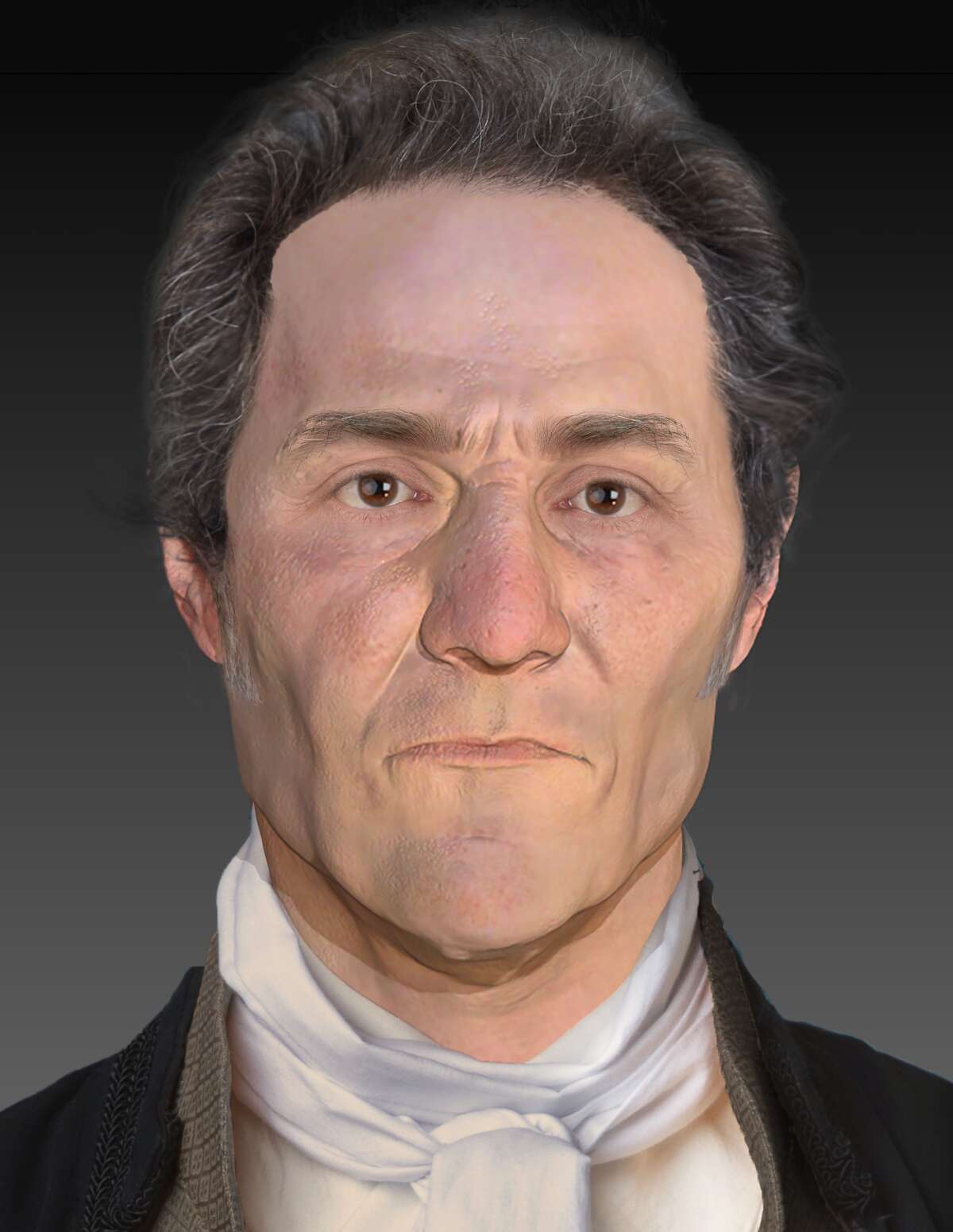

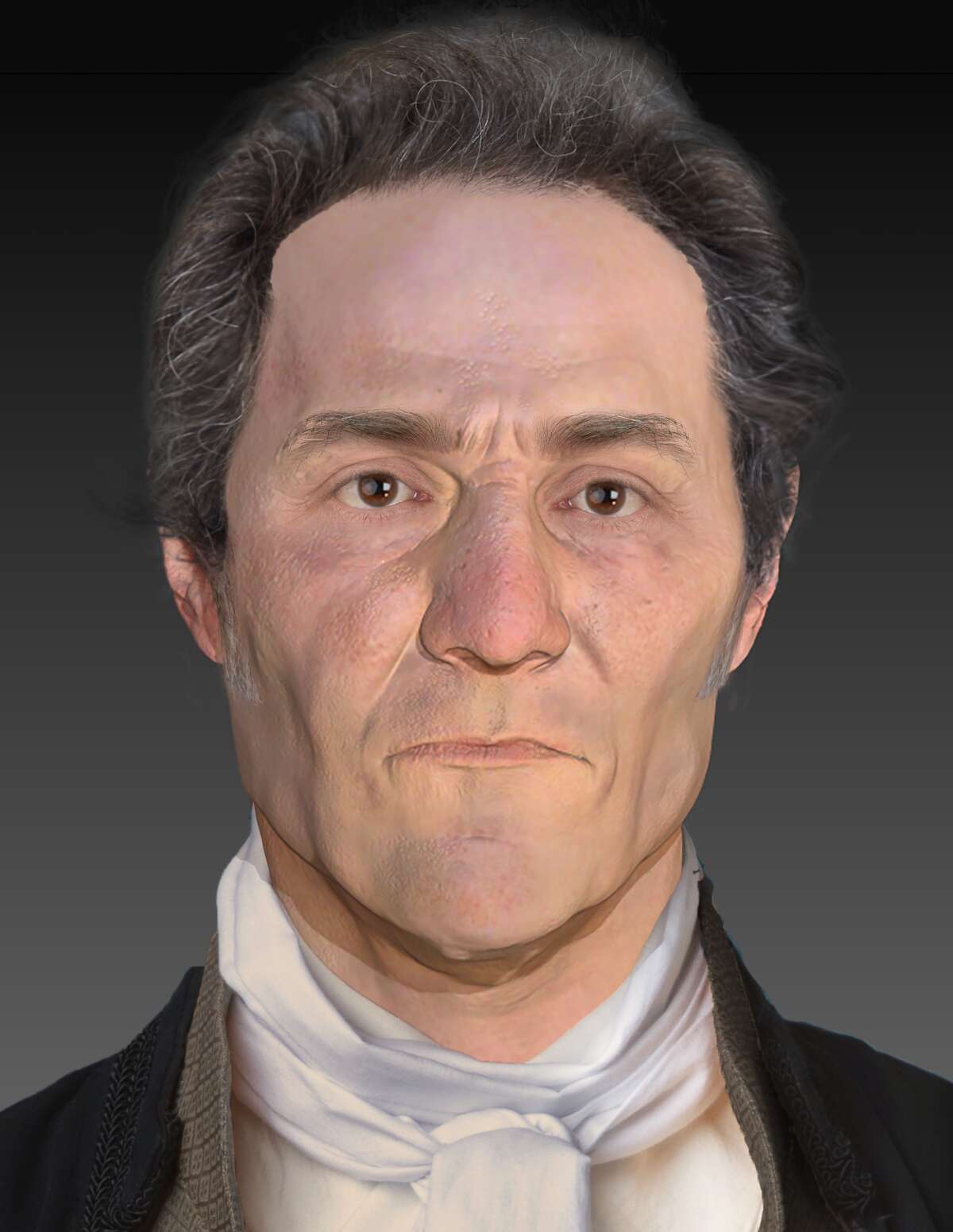

Forensic facial reconstruction/approximation of the appearance of JB55 at age 55. Particulars such as known tooth-loss and inferred health issues informed the final appearance of the image. Hair style was selected based on historical research and styles worn during the early 19th century. Skin, hair and eye color were selected based on phenotype predictions.

Contributed by Parabon NanoLabs

Identifying the Connecticut ‘vampire’

Using genome sequencing, the team at the forensic company Parabon NanoLabs used information from Barber’s remains to find his “genetic genealogy, kinship inference, ancestry and phenotype prediction,” according to a report from company vice president Paula Armentrout. Using these phenotype predictions and 3D images of Barber’s skull, they narrowed down his likely appearance.

They determined he had “very fair/fair skin (92.2% confidence), brown/hazel eyes (99.8% confidence), brown/black hair (97.7% confidence) and few/some freckles (50.0% confidence).”

Last month at the International Symposium on Human Identification, scientists from Parabon and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory showed pictures of what Barber most likely looked like based on that information.

Using GEDmatch, a site used to compare DNA files, they were also were able to trace Barber’s identity to his family tree and determine that another person buried in the Griswold cemetery was likely his first cousin.

Skeletal remains of “JB-55” on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Silver Spring, Md., July 23, 2019.

U.S. Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Robert M. Trujillo

‘The Great New England Vampire Panic’

A fear of vampirism had a grip on 19th-century New England, a period that historians have named the “Great New England Vampire Panic.” The hysteria turned families against one another when they feared that vampires were sickening whole families and killing people off from the grave.

This led people to exhume the bodies of loved ones who were considered “fresh” with blood and, in some cases, behead the corpses and burn their hearts, according to a 2012 article in Smithsonian Magazine.

The truth stems from mass confusion over “consumption” — tuberculosis — that spread throughout households and killed families. Nineteenth century New Englanders did not understand the way that the bacterial infection would spread through the lungs, and it wasn’t until the next century when scientists would make breakthroughs on medicine to curb the spread of the disease.

JB’s grave in Griswold, with his remains arranged by his contemporaries in a manner to prevent the “vampire” from rising and terrorizing the community.

Courtesy of Connecticut Office of State Archaeology

“When we didn’t have the vaccine, people were being sold all sorts of crazy theories — and they still are,” Bell told Hearst Connecticut in October. “It shows kind of the universal aspects of human beings, that when we’re faced with disease and the possibility and probability of death, we have to overcome that fear somehow.”

The myth of vampires spread far beyond the borders of New England, likely inspiring Bram Stoker’s 1897 “Dracula.” The novel likely wasn’t directly inspired by exhumations in New England, but some scholars believe that the character of Lucy was inspired by Mercy Lena Brown, the famous case of “vampiric” exhuming in Rhode Island.