By Andrea Mayes

Photo: Bradley Robert Edwards denies committing the crimes known as the Claremont serial killings. (ABC News: Anne Barnetson)

Photo: Bradley Robert Edwards denies committing the crimes known as the Claremont serial killings. (ABC News: Anne Barnetson)You could be forgiven for thinking the Claremont serial killing case is all but over, the evidence so unlikely to convict accused triple murderer Bradley Edwards that the trial might as well wind up early.

“DNA debacle”, “Huge DNA blow to prosecution’s case” and “Gobsmacking blunders” are just some of the headlines we’ve seen in recent weeks.

But in the context of the marathon trial, likely to span six or seven months, just how important is the DNA evidence, and the errors scientists have admitted making when handling samples from the case?

Here’s a rundown.

So what’s the deal with the DNA?

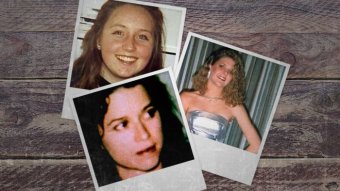

Lawyer Ciara Glennon, 27, was the last of three young women to disappear from the streets of Claremont over a 14-month period from January 1996 to March 1997.

Sarah Spiers. Jane Rimmer. Ciara Glennon. Three women whose names were etched into Perth’s consciousness more than 20 years ago.

It is the prosecution’s case that in a desperate but ultimately futile fight for her life, Ms Glennon scratched or clawed at Edwards and in the process some of his DNA was deposited underneath at least one of the fingernails on her left hand.

Only the bodies of Ms Glennon and childcare worker Jane Rimmer have ever been found. Teenage receptionist Sarah Spiers remains missing.

Despite extensive testing of multiple samples taken from the two bodies and the surrounding areas where they were discovered — analyses that took place over 20 years — only Ms Glennon’s fingernails yielded any useful DNA.

The DNA extracted from a combined sample of Ms Glennon’s left thumbnail and left middle finger is the sole piece of DNA evidence connecting Edwards to the murders.

Hence the protracted amount of time spent on it.

But hasn’t the DNA evidence been contaminated?

That is what the defence is trying to convince Justice Stephen Hall of.

Edwards, a former Telstra worker, admits it is his DNA found on the fingernails and he has no explanation for how it came to be there.

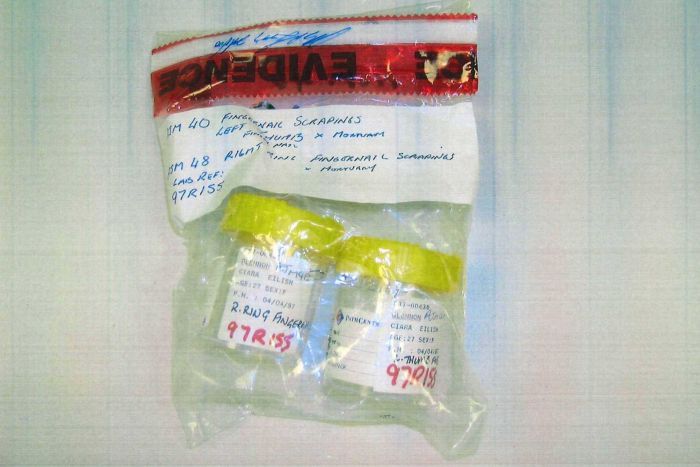

Photo: Fingernail scrapings from Ciara Glennon were sealed in forensic evidence containers. Archive photo (Supplied: Supreme Court of WA)

Photo: Fingernail scrapings from Ciara Glennon were sealed in forensic evidence containers. Archive photo (Supplied: Supreme Court of WA)In his opening, defence counsel Paul Yovich SC said the chance of contamination in a laboratory was remote.

But he said the fact there had been a whole load of other instances of contamination at PathWest involving other samples from the Claremont case meant Justice Stephen Hall would “have to consider just how remote the chance was here and whether it could be safely ruled out, even if it was remote.”

Wait, so what samples were contaminated?

Quite a few of them as it turns out, though it is a small percentage compared to the number of times material from the case has been examined and tested over the years.

In most cases, DNA from a scientist working at PathWest was found on a sample, sometimes years after the event. These are:

- An intimate swab taken from Jane Rimmer found with DNA from PathWest scientist Laurie Webb in it

- Vegetation from Ms Rimmer’s burial site that had DNA from PathWest scientists Louise King and Aleksander Bagdonavicius on it

- Another piece of vegetation from the same site found to contain Ms King’s DNA

- A sub-sample of Ms Rimmer’s hair containing a female PathWest staffer’s DNA

- Another intimate swab, this one from Ms Glennon, found to have scientist Scott Egan’s DNA on it

- A razor taken from Ms Glennon’s house that had Mr Webb’s DNA on it

- An earring found to have been contaminated by scientist David Fegredo

But unusually, there were also a couple of samples found to contain Mr Webb’s DNA despite the fact he never worked on them. These were:

- A sample of Ms Rimmer’s fingernails

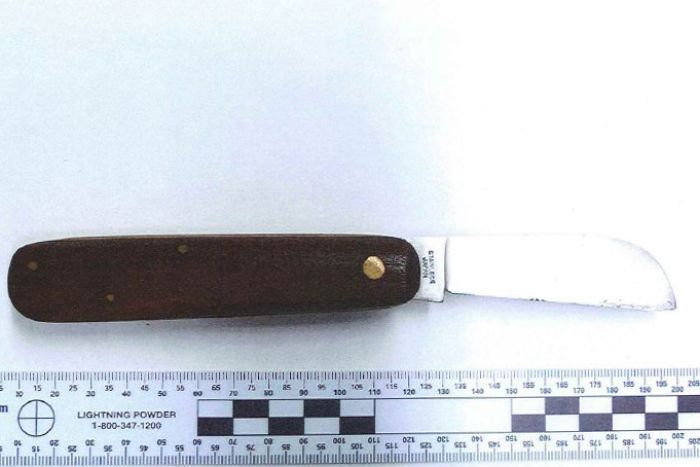

- A knife connected to Ms Glennon

How could this be?

Asked to explain what happened in those instances Mr Egan, who has been at PathWest since 1996, said Mr Webb was “in the vicinity” when the samples were processed, and his DNA could have been on equipment and furniture in the lab.

He also could have sneezed or coughed in the area, which might have transferred DNA to the items, Mr Egan said.

Photo: This Telstra-issued knife was found near where Jane Rimmer’s body was discovered in the outer Perth suburb of Wellard. (Supplied: Supreme Court of WA)

Photo: This Telstra-issued knife was found near where Jane Rimmer’s body was discovered in the outer Perth suburb of Wellard. (Supplied: Supreme Court of WA)And significantly, the scientist agreed with defence counsel Paul Yovich that the transfer could have occurred due to the “natural movement of air”.

Prosecutor Carmel Barbagallo emphatically insisted in her opening address that “DNA within a particular sample did not just fly around a laboratory” — a point reinforced by PathWest scientist Martin Blooms in his testimony last month.

Photo: Edwards admits it’s his DNA on the crucial samples, but disputes how it got there. (Facebook: KLAC)

Photo: Edwards admits it’s his DNA on the crucial samples, but disputes how it got there. (Facebook: KLAC)But if Mr Yovich can show that DNA can in fact be transferred in a laboratory where strict cross-contamination protocols were observed, he may be able to cast doubt on the integrity of the all-important Ciara Glennon fingernail samples.

There is also another documented instance of contamination of a sample by a person who had not come into contact with it.

This is another twig from Ms Rimmer’s burial site which was found to contain the DNA from the teenage victim of a totally unrelated crime in 2002.

It turns out samples from that crime were processed five days before samples from the twig were examined, in the same area of PathWest and using the same batch of single-use sample tubes later used for the Rimmer samples.

Mr Egan agreed with Mr Yovich that DNA being transferred through the equipment was a “highly unlikely mechanism for the transfer of DNA”, but it nonetheless happened.

What about Ciara Glennon’s fingernails?

Amid all these examples of contamination, it is important to note that there has been no evidence that directly proves the crucial DNA evidence on which the state relies has been contaminated.

And there has been plenty of evidence that the chances of Edwards’ DNA somehow contaminating Ms Glennon’s fingernail samples is “very unlikely”.

You might remember that PathWest was already holding samples of his DNA in April 1997 when the fingernail samples first came into the lab, even if they didn’t know the samples were from him at the time.

Bradley Edwards has pleaded guilty to raping a teen girl in a cemetery and attacking an 18-year-old woman in her home.

These were in the form of samples related to the brutal rape of a 17-year-old girl at Karrakatta Cemetery in 1995 — a crime Edwards only confessed to late last year.

Tests were done on intimate samples from the rape in February 1996, and then again in May 1997.

Between February 1996 and April 1997 — when Ms Glennon’s fingernails came into PathWest’s custody — the laboratory had been cleaned “hundreds if not thousands” of times, Mr Egan told the court.

Of the two critical Glennon fingernail samples, one of them — known as AJM 40 (from her left thumb) — was kept in a sterile jar in PathWest’s freezer, unopened and untouched (“pristine”, in Ms Barbagallo’s words), and marked “debris only, not suitable for analysis”.

The other one, called AJM42 — from her left middle fingernail — was opened just twice by PathWest, once on April 9, 1997, and again in 2004.

Time-wise, more than a year elapsed between the rape samples being opened and AJM42 being opened.

“Based on that time frame, I can’t see any viable mechanism for that contamination to occur,” Mr Egan said.

Can DNA ‘jump between boxes’?

Both the rape samples and the two critical fingernail samples were stored in the PathWest freezer, although in different locations.

Could Edwards’ DNA have been “jumping between boxes” in the freezer, as Ms Barbagallo put it?

The short answer is no, Mr Egan said this week.

“The DNA would have to get out of the tube with the lid on it, out of the box that has the lid on it, through the box with the lid on it and then into the tube with the lid closed on it,” he said.

There is also the fact the rape samples contain what is known as “mixed-profile DNA” originating from both Edwards and his young victim — yet none of her DNA has been found on Ms Glennon’s samples.

So will the mistakes sink the prosecution’s case?

It is true that PathWest made a litany of errors relating to the Claremont case, some of them more serious than others.

It was Mr Egan’s evidence that there had been 28 mistakes in the two decades of the case, amounting to an error rate of about 0.16 per cent out of the 17,000 times PathWest staff dealt with Claremont-related items.

This, he said, compared favourably with the error rate from a similar lab in The Netherlands of between 0.3 to 0.4 per cent.

Photo: Paul Yovich SC is trying to cast reasonable doubt in the DNA evidence. (ABC News: Charlotte Hamlyn)

Photo: Paul Yovich SC is trying to cast reasonable doubt in the DNA evidence. (ABC News: Charlotte Hamlyn)However under cross-examination from Mr Yovich, more mistakes were revealed that had not been counted in PathWest’s official statistics.

These included four “blank” samples sent to New Zealand for further DNA testing in 2004 along with AJM42 which were found to contain a staff member’s DNA.

Remember, the onus is on the state to prove “beyond reasonable doubt” that Edwards murdered Ms Spiers, Ms Rimmer and Ms Glennon.

Mr Yovich, on the other hand, needs to sow enough reasonable doubt in Justice Hall’s mind to make any conviction unsafe.

Is there other evidence?

Yes, DNA is just one part of the prosecution’s case, albeit a very important one.

There is also:

- Propensity evidence — the fact Edwards carried out what the state describes as “strikingly similar” attacks on other women, including the 17-year-old girl he snatched from Claremont late at night, tied up and brutally raped.

- The Telstra Living Witnesses — the string of people who testified about a Telstra vehicle acting suspiciously in the Claremont area around the time of the women’s disappearances.

- The “emotional upset” argument — the prosecution’s case that Edwards committed crimes at times of emotional crisis in his life

- Fibres found in the hair of both Ms Rimmer and Ms Glennon — evidence which has yet to be heard — which the state says match fibres from Edwards’s car and clothing.

With the trial not looking likely to end before June, and Justice Hall likely to take months to deliberate on such a complex case, it will be a long while before we know whether the DNA argument has been won by the prosecution or the defence.

Topics: murder-and-manslaughter, law-crime-and-justice, courts-and-trials, perth-6000, wa, claremont-6010