He was jailed for killing her daughter.

Then she feared the police had the wrong man.

CHAPTER 1: THE KILLING

The two colleagues knocked tentatively on the front door. Julia and Tawni, who worked at a beauty store in downtown Idaho Falls, hoped their friend would answer. Angie Dodge had failed to show up for her shift and, after their calls went unanswered, they had rushed to check on her.

Angie’s apartment was on the upstairs floor of a faded wood-paneled building, on a quiet street in the north of the city. It was a hot day in June and the roof above the front porch provided some welcome shade.

There was no answer so the girls let themselves in. They called out for Angie but heard nothing back. Two bags of rubbish sat next to the stove and, on the outside decking area just off the kitchen, a filled ashtray and some plastic cups were evidence of a small gathering the night before.

They made their way down the hallway and checked the living room. Still nothing. Then they headed for the bedroom at the back of the apartment. That was where they found her body.

Angie was lying on the floor with her head up against the wall, next to a mattress that was covered with a blood-stained sheet. Her hands were by her sides and the carpet beneath her was soaked through with blood.

She had been raped and stabbed to death. There was a large cut across her throat and more than a dozen puncture wounds on her body. There was no sign of forced entry in the apartment but there were signs of a struggle.

The police concluded that Angie had been killed between 00:45 and 11:15 on Thursday 13 June 1996. They took away her bedding and clothing for testing and also collected a sample of the killer’s DNA.

“It was a very good one,” said Dr Greg Hampikian, a leading DNA expert who worked on the case. “There was a neat semen sample taken directly from the victim’s body. It was a really good sample. A pristine profile.”

This would prove crucial later on.

The previous evening, less than twelve hours before she was killed, Angie had pulled up outside her mother’s modest, single-storey, house and greeted her with a kiss.

Carol Dodge held her close. The pair had argued, as they sometimes did, but they quickly made up. “I hadn’t seen her in three weeks,” Dodge said. “She was 18 and wanted to be left to grow up on her own. But when she came over it was like nothing was wrong. It was just normal.”

Image copyright Dodge family

Image copyright Dodge familyAngie, the youngest of Dodge’s four children and her only daughter, shared many of her mother’s features, including her piercing eyes, blonde hair and, according to those who knew them both well, her stubborn and straight-talking nature.

“She didn’t put up with people’s crap,” her best friend, Jessica Martinez, said. “She was very smart and one of the only people in our group to graduate high school.”

Angie had recently split from her boyfriend and, a few weeks earlier, had moved into her first apartment. “She told me it was so hard growing up,” Dodge said. “She just put her head on my shoulder and we kinda just rocked back and forth.”

It was still warm outside when Angie said goodbye to her mother and headed for her car. “She threw me a kiss when she coasted out of the driveway,” Dodge said. “Her last words to me were ‘I love you’. I just had no idea what was about to happen.”

“I look at it now as a God-given moment. And I’m so grateful that we got to have it.”

With its largely white, churchgoing, population, Idaho Falls is a typical city for this part of the western US. The downtown area is a mismatched spread of modern drive-thru joints and car dealerships. In the summer, bus-loads of tourists pass through on their way to Yellowstone National Park. The Snake River, flanked by two pristine trails, meanders through the centre of town before it drifts out into the vast plains of southern Idaho.

Christopher Tapp was down by the river when he heard about the murder. A 19-year-old high school drop-out, he was with a group of teenagers known as the River Rats. They were a familiar sight in Idaho Falls, and would spend entire summers joking and drinking by the water’s edge.

Word of the killing had spread quickly, from the worshippers in the glistening Mormon temple to the inhabitants of the myriad one-storey wooden houses, and eventually down to the boat docks, where the River Rats spoke in hushed tones. They knew Angie Dodge well: she was a regular down at the river.

Image copyright Christopher Tapp

Image copyright Christopher TappHer killing left them with more questions than answers. Who could have done this? And why would they target Angie? In a small town like Idaho Falls, where crime was low and everyone knew one another by name, the murder of a teenage girl was unheard of.

But for Tapp, who was drifting between jobs, the murder simply marked another talking point in a long and aimless summer. “I know this might sound bad, but it was just one of those things that happened.”

Yet that stifling summer’s day when he was first told about the killing would stay with him forever. “That was pretty much when everything started,” he said.

The Idaho Falls Police Department pursued a theory that more than one person was involved in Angie Dodge’s killing. They took DNA samples from dozens of men, including the River Rats, but none came back as a match.

The department, which was not accustomed to investigating such a complex and high-profile homicide, appeared overwhelmed by the case. Six months after Angie’s killing there were still no clear leads and frustration was starting to build.

“It makes you wonder what they’re doing, if they’re doing anything,” Carol Dodge told the Idaho Statesman at the time. “They’re just not qualified. These detectives are street cops that have been promoted.”

“What do we do? Where do we go?” she said. “I can’t think of what to do.”

But she soon had an idea. Dodge, a broad woman with a frank way of speaking, distributed thousands of fliers offering a $5,000 reward for tips. When little came of this, she took to patrolling the streets until the early hours and asking anyone who would listen if they had information about her daughter’s death.

Niki Chan Wylie

They would just laugh at me. They called me a crazy grieving mother.

Dodge would often barge into the local police station unannounced and demand to know what the department was doing to find Angie’s killer. This was not always welcome. The rear door of the building was jokingly renamed the ‘Carol door’ by officers due to her frequent guest appearances.

“I would just march right in there where the detectives were, and they’d be sat with their feet up on the desk, and I’d ask them who they’d talked to and what they were doing to solve the murder,” Dodge said. “I’d say: ‘Well you just sit right there, because I’m going out tonight.’ They would just laugh at me. They called me a crazy grieving mother.”

Angie’s family was frustrated and wanted answers. The press headlines, too, remained critical of the police department. Months went by until one man was dragged into their investigation.

CHAPTER 2: THE CONFESSION

January 1997, seven months after the murder of Angie Dodge.

In neighbouring Nevada, Christopher Tapp’s best friend, Benjamin Hobbs, was arrested for raping a woman at knifepoint. Investigators thought this crime resembled the killing of Angie. Hobbs, who was from Idaho Falls and knew her well, became their number one suspect.

The police tried to build a case around him and Tapp was asked to come in for questioning.

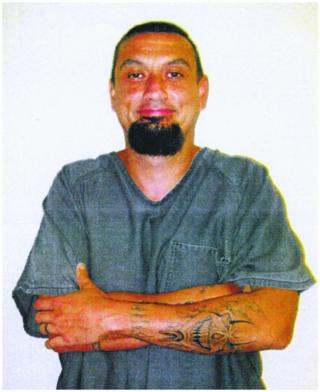

Image copyright Bonneville County Jail

Image copyright Bonneville County Jail“I instantly said: I don’t know anything. I can’t help you. I have no idea what you guys are talking about’,” Tapp said. He told them he had been with a girl on the night Angie was murdered.

But the detectives, who had initially just wanted to ask him about Hobbs, came to believe both men had been involved in the killing. They wanted to see if Tapp had any information implicating his friend, although Tapp continued to deny all knowledge of the crime.

Tapp trusted the police officers – one of them had worked at his high school – and so he continued to co-operate. Over three weeks, he was interrogated nine times and forced to take seven lie detector tests. His lawyers would later say that he spent more than 100 hours under intense police questioning.

Video of those interrogations show an exhausted Tapp, his boyish face in his hands, crying and barely able to speak. “I was broken,” Tapp said years later. “There is no other way to explain it. I was just broken and confused and scared. I just wanted to get away from them.”

The detectives offered him full immunity – meaning he could not be jailed – as long as he told the truth. When he continued to deny all knowledge of the crime he was told by a polygraph examiner he was failing the tests. “The machine never lies,” the examiner said.

He told investigators what he thought they wanted to hear. He said Hobbs had murdered Dodge. Then, after further polygraphs and interrogations, and after one detective threatened him with the “gas chamber”, he said he had been in the apartment with Hobbs when Angie was killed. He told six different stories.

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie / BBC

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie / BBC“I just gave them whatever information they wanted because I thought it would get me out of the situation,” Tapp said.

But there was a problem. DNA tests on Tapp and Hobbs came back negative – it was not their semen at the crime scene. The detectives, now on the back foot, suggested a third man may have been involved. Tapp implicated another friend, a man called Jeremy Sargis, but his DNA test was also negative.

The detectives claimed Tapp had been untruthful and voided his immunity agreement completely.

During a polygraph test on 30 January 1997, Tapp denied eight times that he had stabbed Angie Dodge. The police told him he was facing the death penalty and could get a more lenient sentence if he said he had feared for his life during the attack. Tapp was told he needed to admit this to save his life.

Detective: If you were forced to do it in fear of your own life, that’s a different story. We could go with a different charge rather than life imprisonment or death.

I’m a cop, I shouldn’t be saying this, but I’m kinda close to you. You gotta save your life, period. You got forced into doing something you didn’t want to do. Protect your own ass. You got trapped.

Tapp: Alright.

Detective: Did Ben Hobbs force you to cut Angie Dodge across the right breast with a knife or he said he would kill you?

Tapp: Yes.

After this apparent admission, Tapp asked how he had performed and the detective shook his hand. Hobbs and Sargis were both released, but Tapp, to his surprise, and despite the fact that no physical evidence linked him to the scene, was charged with murder and rape.

“I tried to save myself and just continued to put myself further and further down the rabbit hole,” he said. “Then they actually charged me. It was heartbreaking. I knew that this might be the end.”

The trial began in May 1998. Tapp, who arrived wearing a baggy navy blue suit and matching tie, maintained his innocence throughout. He said his confession was coerced and his DNA test proved he wasn’t the killer. “The hardest thing was watching my mother sit there while people looked at me like I was a monster,” he said.

“Everybody was watching the news reports,” said Vicki Smith, the court bailiff who worked the trial. “But I looked at Chris and his behaviour, and I looked at his attorney, and I just felt like things weren’t – I can’t explain it – it just didn’t feel normal.”

Niki Chan Wylie

They actually asked to kill me.

The defence tried to get Tapp’s confession thrown out, but the judge refused and it was admitted as evidence. As well as the confession, the police introduced the testimony of a young woman named Destiny Osborne who said she had heard Tapp talking about the killing at a party. She would later retract this statement and allege that the police had pressured her to testify.

It took the jury a little more than 13 hours to find Tapp guilty of first-degree murder, rape, and the use of a deadly weapon in the commission of a felony.

When the unanimous verdict was read out, Tapp fell to his chair and held his head in his hands. “There was a humongous picture of me in the newspapers and you can see me with tears in my eyes,” he said. “It was heartbreaking to know that I was going to go to prison and that might be the end of me.”

Tapp was sentenced to life in prison. “One thing that I never really talk about is the fact that they asked for the death sentence,” he said. “They actually asked to kill me.”

Following the verdict, Vicki Smith escorted the jurors out of the courtroom. “Two of them collapsed on the floor and were crying and sobbing,” she said. “I think the look on Chris’s face, the fact he was crying, and the fact he was so young was overwhelming for them. I don’t think they wanted to find him guilty, but there was nothing in the trial that proved he was innocent.”

Carol Dodge, the victim’s mother, glared at Tapp throughout. She stormed out after the verdict and threw her hands into the air in frustration as she passed rows of cameras and reporters. After all, there was no physical evidence linking Tapp to the scene and he didn’t match the DNA found on her daughter’s body.

“I believed the investigators when they told me that there was another person who left the DNA,” she said. “I was so angry at Chris for not giving that person up. I couldn’t understand why he wouldn’t just give us the name.”

“Before the trial, I wrote him a letter when he was in prison and I said: ‘Chris, I don’t know why you won’t give up the name of this other person.’ I was so angry at him.”

Nearly two years after Angie Dodge was murdered, Tapp was sent to prison and the case went cold. But Carol Dodge was determined to find who left the DNA at the crime scene. “I wasn’t going to go away,” she said. “I was driven to find justice for my daughter.”

CHAPTER 3: A MOTHER’S SEARCH

Nothing came of Dodge’s early efforts to find the other person involved in Angie’s murder. Tapp, meanwhile, spent years in a maximum-security jail, first in Kuna, Idaho, and then in Texas, and had little hope of getting out.

His lawyers filed appeals based on different aspects of his trial but none was successful. The case came to a standstill: Dodge was desperate to find the DNA match and Tapp was desperate to get out of prison. Neither outcome seemed likely.

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie / BBC

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie / BBCIn 2009, more than a decade after Angie’s death, the killer’s DNA was entered into a national crime database but there was still no match. A few years later, Dodge was gifted a computer for Christmas. There was little doubt what she would use it for. “I was always looking on there for ways that I could solve my daughter’s murder case,” she said.

She found a company in Florida that could identify the race of a DNA sample, and the police agreed to the test. The result found the unknown person was 85% Caucasian. “That cut down on a lot of leads,” she said.

But this wasn’t enough. Dodge knew she had to get the attention of some well-known experts. “I knew something wasn’t right so I really started to study DNA. I spent hours and hours, sometimes whole nights, researching it.”

She eventually came across Dr Greg Hampikian, one of the country’s leading forensic DNA experts. He had founded the Idaho Innocence Project, which works to correct and prevent wrongful convictions.

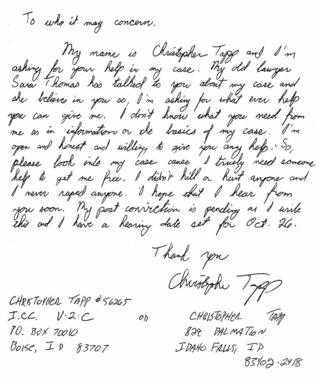

Hampikian was already well aware of the case. Tapp had written to the Idaho Innocence Project from prison a few years prior to beg them to investigate his conviction. “I didn’t kill or hurt anyone and I never raped anyone,” his letter said. “Please look into my case. I truly need someone to help get me free.”

Image copyright Christopher Tapp

Image copyright Christopher Tapp

“I asked one of my interns to look at the interrogation tapes,” he said. “She called me up, almost crying with excitement, and said: ‘This guy’s innocent. They fed him everything.’ So we took the case.” It was the first time a victim’s family had worked with an innocence organisation anywhere in the US.

By then, there had been huge advances in DNA technology. With help from Hampikian, Dodge pushed the Idaho Falls Police Department to try something called familial DNA testing. This involved looking at the database of convicted offenders in Idaho for anyone who might be related to Angie’s killer.

After two years of legal wrangling, the state refused to allow access to its criminal database for this kind of testing. So Hampikian came up with a more radical idea. He suggested uploading the crime scene sample to public databases, such as those owned by Ancestry.com.

Crucially, the police were on board with this plan. “We were pushing hard. Carol was pushing hard,” Hampikian said. But it initially proved to be another source of frustration.

One database threw up a compelling suspect – a filmmaker from New Orleans. He had visited Idaho Falls in 1996 and had even made a short film about the violent murder of a young girl. But DNA tests came back negative and the police were back to square one.

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie

Image copyright Niki Chan WylieDespite this, investigators in Idaho Falls weren’t ready to give up on this new method. In fact, they were more determined than ever.

Carol Dodge, meanwhile, was confused. She was desperate to find a match to the DNA at the crime scene but she wasn’t ready to accept that Tapp was innocent. The prosecutors may have been right, she thought. Perhaps he had killed Angie with someone else and was afraid to give that person up.

“I believed for so many years that Chris was part of Angie’s killing,” she said. “They had me convinced that he didn’t act alone. But my mind changed after I sat down and listened to the confession tapes.”

Niki Chan Wylie

There’s major league brainwashing and manipulation going on.

A local newspaper, the Post Register, had obtained the tapes through the Freedom of Information Act and shared them with Dodge. There were more than 25 hours of footage, all on VHS tapes, with terrible sound quality and no subtitles. Still, Dodge was blown away by what she saw.

“I probably had those tapes for years before I actually sat down and went through them,” she said. “But when I did I got so mad at [the police] because they’d ask Chris a question and then they’d answer it for him.”

The tapes left Dodge with major doubts about whether Tapp had killed her daughter. She contacted false confession experts so she could fully understand what she had watched.

Among them was Michael Heavey, a retired judge who founded Judges for Justice, which works to overturn suspected wrongful convictions. “He spent hundreds of hours going through the tapes and putting it all in perspective for me,” Dodge said.

Image copyright Judges for Justice

Image copyright Judges for JusticeHeavey became convinced Chris Tapp was innocent. He worked for more than two years to prove the confession had been coerced. “It kept jumping out to me that this guy didn’t know anything,” he said. “Chris told six separate stories. He goes from saying he wasn’t there to confessing that he stabbed her. I thought: ‘Why is he constantly changing it?'”

Heavey noticed red flags in the police questioning and came to believe Tapp was tricked – even brainwashed – into giving false testimony. “He thought the polygraph was an all-knowing, scientific, instrument that was reading his subconscious and telling him he was at the murder of Angie Dodge.

“They manipulated him into believing he was suppressing memories of being at the crime,” Heavey said. At one point, a detective tells him he might have blacked out the memories due to trauma.

“There’s major league brainwashing and manipulation going on,” Heavey said. “It’s ugly stuff.”

The BBC asked an independent false confessions expert to review some of the footage of Tapp’s interrogation. Professor Allison Redlich, from George Mason University in Virginia, shared many of the concerns Judge Heavey and others have raised.

“It was very coercive and, frankly, unconstitutional when they threatened him with the death penalty during a polygraph,” she said.

Prof Redlich also flagged the sheer length of time that Tapp spent under interrogation as a risk factor. “Certainly longer interrogations with somebody who is innocent can lead to false confessions, because the person’s resolve just weakens over time,” she said.

“I noticed that [the police] also provided details of the crime to Chris and asked leading questions,” Prof Redlich said. “They showed him pictures of the crime scene, supposedly to jog his memory, and that absolutely should not be done. You can see that he starts to distrust his own memory.”

The current Idaho Falls Police chief, Bryce Johnson, recognised mistakes were made in the Tapp interrogation but said the force’s methods had changed since 1996. “Clearly something went wrong there, but there are a lot of differences in terms of what happens today,” he said.

He also pointed to a failure on the part of Tapp’s original lawyer. “I don’t think you’d find a defence attorney that would allow a client to sit there and talk to the police like that today,” he said. “I just don’t think you would.”

Watching the tapes left Dodge with a burning question. She now doubted Tapp had killed her daughter, but couldn’t be sure. Then, during dinner one evening, Heavey received a phone call from Tapp and she snapped.

Image copyright Christopher Tapp

Image copyright Christopher Tapp

“I took the phone outside and I just blasted Chris.

“I said: ‘Look, you little son of a bitch, you were either there or you weren’t. Quit playing the frickin’ games. If you were there, my God, you’re gonna die if you don’t give me the name of who you were with. And if you weren’t there, then you better frickin’ start screaming that you weren’t.'”

Tapp told her he wasn’t. “I think that’s when it all changed,” she said.

In a remarkable step, Dodge went public and said she believed that Tapp – who had spent almost two decades in jail for the murder of her daughter – was innocent.

“It’s like a film,” she said. “Imagine sitting in your theatre seat thinking: ‘My God what’s gonna happen now? What is she doing?’ It’s just crazy.”

CHAPTER 4: GETTING OUT

Carol Dodge’s efforts to rally experts and keep the story in the news meant that by 2016, there was a chorus of criticism aimed at Tapp’s conviction. In May that year, his attorneys filed an appeal.

They asserted Tapp’s confession was the result of police coercion and said videos of the polygraphs had been withheld from the original trial. They hoped new DNA samples from Angie’s hands would prove he was not the killer.

The team, led by John Thomas, believed they had a strong case. “The Tapp name was synonymous with false confessions and bad attorney work,” he said. “This kid was railroaded.” But their appeal was put on hold when Thomas received a surprise phone call.

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie

Under growing pressure from Carol Dodge, the lawyers, and the Idaho Falls community, and with the threat of a lengthy appeals process looming, county prosecutor Daniel Clark offered a deal for Tapp’s release. He would be free, but his convictions would stay on his record and he would be put on parole for at least 10 years.

After much deliberation, Tapp turned the deal down because he wanted to prove his innocence through the courts and clear his name. “It was total bravery,” John Thomas said.

But then Thomas convinced the prosecutor to agree to another deal: Tapp would lose the rape charge, keep the murder charge and walk free after 20 years in prison. And if the police ever found the real killer, Tapp would be exonerated.

Tapp agreed to the deal.

“Everyone wanted me to come home totally free,” he said. “But they didn’t understand. That was my opportunity; no more looking over my shoulder, no more lock-down in my cell, no more crappy food in the chow hall.”

The guards came for him first thing in the morning. It was 22 March 2017, and it was shaping up to be an unseasonably warm day in Idaho Falls. “Tapp, we need you out here,” one guard called out. “We’re gonna take you to court.”

Inside the courtroom, Carol Dodge was visibly emotional as she addressed Tapp, who wore a new white button-down shirt and black trousers his mother had brought him. “Go forward without bitterness and without a hardened heart,” she told him. “From this day forward it’s up to you – the path that you choose.” She left the stand and the courtroom stood in silence.

Image copyright Alamy

Image copyright AlamyShortly after, following a statement from the judge, Tapp was free.

In the lobby, he was met by a throng of national media as well as applause and cries of ‘Freedom!’. “They were all asking me how it feels and if I was ready,” Tapp said. “But the truth is I was ready in 1997.”

Dozens of people were waiting outside. “This is it, Chris. Freedom!” Thomas cried, as he held his client’s hand aloft.

Tapp, who appeared taken aback by the applause, gave a short statement on the courthouse steps. “I want to prove to everybody that I can be something and do something right,” he said. “I’m thankful for all the time and energy Carol has given me to help me get to this point.”

He spent more than an hour hugging and chatting to his supporters. His mother, Vera, offered to take him for pizza. Tapp said he wanted steak instead. A gaggle of reporters followed him to the restaurant. “It was really humiliating,” he said. “They’re holding the cameras and wanting to watch me eat but you don’t get metal utensils in prison. I had to learn how to cut up my food on camera!”

“The world had changed,” he said. “Cell phones ruled the world and there was no more physical talking between people. That really bothered me when I first got home. Plus, in my mind I was still a 20-year-old kid, but all my friends had kids, mortgages, and car payments. They had real lives.”

Image copyright Alamy

Image copyright Alamy

Despite this, Tapp was delighted to be free. But he was still a convicted murderer, and the county was keen to emphasise he had not been cleared. “There is not sufficient evidence to prove Tapp is innocent,” prosecutor Daniel Clark said at the time.

Carol Dodge, however, was dead set on finding that evidence. “Without finding my daughter’s killer and matching a person to the DNA,” she said, “could we ever prove that Chris wasn’t there?”

CHAPTER 5: THE HUNT

In summer 2017, the Idaho Falls Police Department got a new police chief, Bryce Johnson. The investigations bureau was also refreshed, and one officer who had been a rookie cop at the time of Angie Dodge’s murder was made its captain.

“Shortly after I got here Carol Dodge reached out to me,” Johnson said. “She introduced herself and we spoke a couple of times. She put her arm around me, she told me that she loved me, and I thought, ‘I’m an American police officer, don’t touch me!'” he joked.

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie / BBC

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie / BBC

“But I realised she was sincere. It was clear that she absolutely loved Angie and this story had dominated her life for decades,” he said. “Carol made all of us want to do our best for Angie. She had an immense influence on us.”

The department set about finding who had left the DNA sample.

New technology – genetic genealogy – was gaining traction in the US. It had been used to snare a suspect in the Golden State Killer case in California, when a man believed to be behind 12 murders and 45 rapes was detained. The method involves comparing DNA evidence found at crime scenes to personal DNA that individuals submit to commercial websites like Ancestry.com.

The department made genetic genealogy a central part of its investigation.

In late 2018, the police partnered with CeCe Moore, a DNA expert who regularly appeared on big-name TV shows. Moore – with her curly blonde hair and pearly smile – was one of the best-known faces in genetic genealogy. She had cracked cold cases across the country, but turned down the Dodge case over concerns the DNA samples were too degraded.

“Then Carol reached out to me,” she said. “She begged me to try and make it work and do everything I could to find her daughter’s killer. I felt a tremendous amount of pressure. I didn’t want to let her down.”

In summer 2018, Moore uploaded the DNA to a database called GEDmatch, that allows users of websites like Ancestry.com to compare their results with others. Despite her concerns about the quality of the sample, it worked.

She started building genetic networks, that let her see who shared DNA with the unknown suspect. Those matches would then be traced back to a common ancestral couple. This family tree could, in theory, lead Moore to Angie’s killer.

Moore soon established the suspect had to be the grandson or great-grandson of a man called Clarence Ussery. Using birth certificates and obituaries, she mapped all his descendants who would have been the right age at the time of Angie’s death in 1996. She narrowed it down to six men – one of whom lived in Idaho.

CeCe Moore

I had hit a brick wall… for the first time in my career.

She gave the name to the Idaho Falls Police Department, who then needed to get a DNA sample from him. They tailed the suspect for days.

“I told Carol that it was looking good and we were going to be able to find the killer,” Moore said. “I told her: ‘I’m gonna do this, Carol, I’m gonna finally find this guy and you’re gonna finally get justice and answers.'”

But they would have to wait. In an enormous blow for the new investigation, the results excluded the suspect, his family and all six men Moore had on her list. “I was so sure he had to be in the family,” Moore said. “It was devastating. I had hit a brick wall. It appeared that genetic genealogy might have led me wrong for the first time in my career.”

The bad news hit Dodge hard.

“I woke up at three o’clock in the morning, drank a Coke, and sat at my kitchen table and started to sob. I said: ‘Angie, I’m so sorry. I’m tired and I don’t know where to go.’ I literally felt her looking down on me and saying: ‘Mom, you’re almost there. You’ve come so far. You can’t stop now.'”

Moore went back to the family tree she had built and looked for anything she might have missed. “One thing that had always bothered me was a really early marriage in the family,” she said. “They had split up and there were no recorded children. But I couldn’t trace the wife and couldn’t find what happened to her.

“I wanted to be sure that there wasn’t a child born to that marriage that went with her. I knew there was a chance he could have been raised by another man.”

They found what they were looking for in a small library in Missouri. Moore’s assistant called to say she had found an obituary for the woman in question. Not only did it say the surname she had taken – Dripps – but it said she had had a son and a grandson. “We looked up the grandson and found that he had been raised with his stepfather’s surname,” Moore said. “His mother had taken him and he never had any contact with the original family.

Image copyright CeCe Moore

Image copyright CeCe Moore

“Then we found that he had lived in Idaho Falls. He didn’t just live in Idaho Falls, he had lived there in 1996.”

“I started crying,” Moore said. “I was on an aeroplane trying not to make a scene. I just kept thinking about what this would mean to Carol.”

Moore held a video call with detectives in Idaho Falls and explained how she had got the new name – Brian Leigh Dripps Sr.

“I got choked up for a minute and even they started crying,” she said. “We all just wanted it for Carol. But that’s where my work ended and theirs began. Now they had to try and build a case.”

The police researched the name Moore had given them and were stunned by what they found. They discovered Dripps had been interviewed as part of a neighbourhood canvas just five days after Angie’s murder in 1996. Not only that, but an old pawn shop receipt and some utility records showed he had lived opposite her at the time.

“It became pretty clear that this might be the person we are looking at,” Johnson said. “At that point the investigation really kicked into hyper-drive.”

In May 2019, a major police operation was launched to get a sample of his DNA. Dripps lived in Caldwell, a five-hour drive away on the other side of Idaho.

Within the first hour of police watching him, he threw a cigarette butt out of his car window. An officer raced into the road to retrieve it but it was lost among dozens of others as traffic raced by. The police had to watch him for another 24 hours before they got a second chance.

On the afternoon of 10 May, detectives saw Dripps discard another cigarette butt out of his car window. As soon as he had driven off, an undercover officer rushed into traffic to recover it. Other officers in plain clothes blocked cars from running over the sample or injuring the detective. It was recovered, and immediately sent for testing.

“We had talked to the Idaho State lab and they knew how important this case was to the community,” Johnson said. “They knew Carol and wanted to do their best for her.” The lab stayed open late into the evening and staff worked through the weekend to extract the DNA and compare it with semen and hairs left at the crime scene.

After more than two decades and 100 DNA samples, the test came back positive. Dripps was a match.

Image copyright Idaho Falls Police

Image copyright Idaho Falls Police

“We were pretty happy about it,” Johnson said. “But we didn’t start partying yet.” The department plotted a second operation to arrest Dripps in Caldwell. They knew he went to a convenience store every day at about 12:00, so the plan was to arrest him on his way out.

“But instead of turning left he turned right,” Johnson said. “We drove forever. At one point he went down a dead end road and we wondered if he knew we were behind him.”

Eventually, Dripps went into a bank and the detectives stopped him as he left. He agreed to answer some questions and, after an interview that lasted for more than five hours, and after he was presented with the DNA evidence, he asked if he could have a cigarette. “I’m sure you want to get this on tape,” he then said, according to one of the detectives who questioned him.

Dripps then confessed to the rape and murder of Angie Dodge and said he acted alone.

“You got me dead right on the DNA,” he told the officers. He was charged that night. His trial is set for June 2021 and he has pleaded not guilty. He is facing the death penalty if convicted.

CHAPTER 6: JUSTICE

It was getting late when Chief Bryce Johnson returned to Idaho Falls. He knew he still had a major job to do, and the first step was to speak to Carol Dodge.

“I told her we had a DNA match and the person was in custody,” he said. “It was pretty emotionally overwhelming for her.”

But he didn’t tell her the name until the next morning, shortly before a press conference about the arrest. Dozens of members of the Dodge family, as well as CeCe Moore and other experts who had worked on the case, all gathered in a crowded briefing room to hear the news.

“I expected five or six people, but there was everybody there,” Johnson said. “We couldn’t fit everyone in. Carol had so many people that she had affected over the years that were part of this story.”

Then he told her.

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie / BBC

Image copyright Niki Chan Wylie / BBC“Chief Johnson said the new suspect was Brian Leigh Dripps Sr and I practically came off my chair,” Carol said. “I said: ‘Brian Dripps? You’ve got to be shitting me. I begged them to take his DNA at the time and they told me to let them do their jobs. I’m still angry over it.

“I’m angry at what they did to me, when they could have solved this case 23 years ago. I’m angry at those two cops who didn’t even write a field report when they spoke to him.

“He was right there all along,” Dodge said, as she started to cry. “I sat in front of his house for hours. Right after we buried Angie, I drove over to her apartment just to sit and look at her bedroom window. And I was sitting in front of his house. It was so close but yet so far.”

The new evidence prompted Tapp’s legal team to push for a full exoneration. He still had a murder conviction against his name and his lawyer John Thomas wanted this cleared. A motion dismissing all charges was finally granted in July 2019 and Tapp – who had spent more than half his life in prison – was finally declared an innocent man by a judge.

Niki Chan Wylie

I was able to tell my mom that my name is clean. That was the most important thing to me in this world.

Tapp’s friends and supporters, who wore T-shirts emblazoned with ‘We told you so!’ and ‘Innocent’, cheered in the courtroom as the news was delivered. Tapp broke down in tears and his mother, Vera, kissed him on the head. Carol Dodge, meanwhile, wiped tears away from her eyes as the man she had once believed had killed her daughter celebrated his innocence.

“I was able to tell my mom that my name is clean,” Tapp said. “That was the most important thing to me in this world.

“I’m so thankful and grateful for what everyone has done for me,” he said. “But Carol: she has been like a second mom. If it wasn’t for Carol’s perseverance and drive then none of this would have ever transpired for me. If she hadn’t sat down and watched the interrogation tapes, and seen how bad it was, then none of this would have happened. I’m so in debt to her.”

The pair embraced after Tapp was exonerated, a moment two decades in the making. “I was really, really happy for Chris,” Dodge said. “I could see that her mother finally had her son back.”

When she reflected on the journey that had led to that moment, Dodge paused and breathed a heavy sigh. Her voice grew louder and more forceful.

“My fight was to find my daughter justice,” she said. “Every road I went down somebody tried to put up a barricade or a roadblock. Everywhere I turned somebody said you can’t do this or you can’t do that. I said: just stand back and watch me do it.”

Image copyright Alamy

Image copyright AlamyChristopher Tapp plans to sue the city of Idaho Falls and that action is ongoing. His story has inspired a new bill that aims to ensure wrongfully convicted people in Idaho are fairly compensated by the state.

Carol Dodge has launched a fundraising project, 5 for Hope, which is raising money to solve cold cases around the US. The challenge is enormous. Between 1980 and 2008, there were an estimated 185,000 cases of murder and manslaughter that remained unsolved.