South Dakota (NBC)(03/16/20)— On Feb. 11, 2019, undercover detectives removed the trash from outside a 57-year-old paralegal’s home in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in hopes of finding her DNA.

Police were led to Theresa Bentaas’ home by a new investigative technique that combines direct-to-consumer genetic testing and genealogical records.

The detectives believed they were close to solving a crime that had haunted the city for 38 years: a newborn left to die in a frigid roadside ditch, tears frozen to his cheeks.

Once they’d taken the garbage from Bentaas’ home, the detectives pulled out beer cans, water bottles, and cigarette butts, according to court documents.

They sent the items to a state crime lab, where analysts extracted DNA that they said might belong to the baby’s mother.

Citing those results, one of the detectives got a search warrant to obtain a DNA sample directly from Bentaas.

When he showed up at her home, Bentaas admitted to leaving the baby in the ditch in February 1981 after secretly giving birth, saying she’d been “young and stupid” and scared, according to an affidavit submitted by the detective.

A few days later, according to court documents, Bentaas’ DNA swab revealed her as the baby’s likely mother. Police then arrested her for murder.

Bentaas has since pleaded not guilty, and now, on the eve of her trial, she is fighting the charges against her.

One of her main arguments is that police violated her constitutional protections against unreasonable searches when they used her trash to find her DNA and develop a genetic profile, without first asking a judge to sign a search warrant.

“People do not have a privacy interest in the things they throw in the trash, but they definitely have privacy interest in their DNA that is on those items,” Bentaas’ lawyer, Clint Sargent, said in an interview. “And there’s nothing a free person can do to not deposit DNA on the stuff they deal with every day.“

The Minnehaha County prosecutor handling the case against Bentaas did not return a request for comment. Neither did a spokesman for the Sioux Falls Police Department.

The practice of going through a potential suspect’s garbage for evidence is not new, but it is facing new scrutiny from civil liberties groups and privacy advocates who see danger in law enforcement’s unchecked power to obtain people’s DNA, which is unavoidably left on just about everything anyone touches, without them knowing about it.

The tactic has grown more frequent with the increased use of investigative genetic genealogy, which relies on DNA and ancestry records to find people with links to DNA left at a crime scene.

Police try to confirm the connection by obtaining the person’s DNA, often through surreptitious means.

“Without protections, every one of us is vulnerable to having our DNA secretly tested and scrutinized by police without judicial oversight,” said Nathan Freed Wessler, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union, who specializes in technology and privacy.

The ACLU, along with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital rights nonprofit, filed a joint brief Monday in the Bentaas case in Second Judicial Circuit Court in Minnehaha County, arguing that while it is legal for police to rifle through someone’s trash for evidence, “extracting and sequencing a DNA sample found on that item” should first require going to a judge for a warrant. Not doing that, the groups said, violates the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

The filing is the first in what the groups say will be a national effort to challenge cases in which police have used trash and other abandoned items to secretly access a potential suspect’s DNA.

Among the cases they are watching is the upcoming trial of an Orlando, Florida, man charged with the 2001 killing of a college student.

The goal, they say, is to persuade judges to require police to first come to them for permission, in the form of a warrant.

“Our DNA can reveal so much about us that our genetic privacy must be protected at all costs,” an Electronic Frontier Foundation lawyer wrote in a blog post this week.

Prosecutors say that argument is a stretch. They point out that the Supreme Court has ruled that it is OK for police to search through someone’s garbage, and criminal defendants have largely failed in the past to challenge the collection of DNA from trash and other items.

The Minnehaha County state’s attorney made those assertions in a brief opposing Bentaas’ motion to suppress the DNA evidence against her.

Duffie Stone, president of the National District Attorneys Association and a prosecutor in South Carolina, said police are allowed to go through someone’s trash or collect abandoned objects, regardless of whether they use those items to find DNA.

Making it more burdensome to test abandoned items for DNA would slow criminal investigations, which often rely on trying to find DNA not only from things left in the trash but also all sorts of objects found at crime scenes, from guns to gum, Stone said.

“They’re trying to extend the expectation of privacy to shedded DNA cells,” Stone said. “I don’t think the courts are going to go with that, and from a practical standpoint it would be impossible for law enforcement to work with that on a regular basis.”

Elizabeth Joh, a professor at the University of California, Davis School of Law, who studies criminal procedure and police surveillance, said that as covert collection of DNA becomes cheaper and easier, there need to be more rules, from the courts or lawmakers, covering it.

“There is basically nothing regulating or guiding the police on what to do other than their own internal guidelines,” Joh said.

On Friday, Bentaas’ defense team and Minnehaha County prosecutors argued the DNA collection issue before Second Circuit Court Judge Susan Sabers, who said she’d make a decision by Tuesday, Sargent, Bentaas’ defense lawyer, said.

Bentaas’ trial is scheduled to begin April 20.

The trial could mark the final chapter in a mystery that has haunted Sioux Falls for nearly four decades.

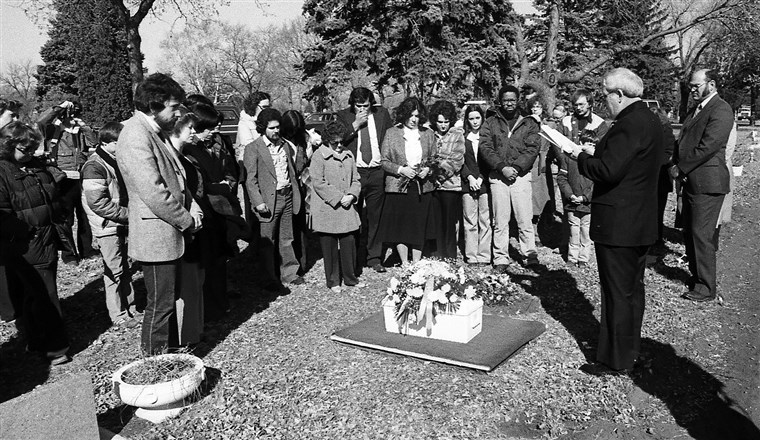

The baby died years before DNA became a crime-solving tool. Residents arranged for a funeral and burial and named the boy Andrew, which was inscribed on his gravestone.

In 2009, a detective, hoping to use new DNA analysis methods to find a new lead, arranged for the body to be disinterred, according to court documents, but the baby’s DNA profile wasn’t closely related to any profiles in the state’s crime database.

Last year, police turned to investigative genetic genealogy, which seeks DNA links outside of crime databases.

Investigators built a family tree that pointed them to Bentaas, according to court documents.

Her arrest triggered a wave of relief across Sioux Falls.

Lee Litz, who found the baby at the side of the road, told a reporter last year that he considered the boy his “long-lost son” and saw Bentaas’ arrest as justice for a community that refused to let his death go forgotten.

“There are times when I wish I hadn’t found him and there are times that I’m glad I did,” Litz told the Argus Leader newspaper. “I just wish I found him earlier, when he was still alive.”

Stay up to date with the latest news by downloading the KTVE/KARD News App from the App Store or Google Play.